Bazel in Action

- 构建基础知识

- TL;DR (Bazel 构建需要完成的三件事)

- Bazel 构建优化方案

- Bazel 安装 (CentOS 环境)

- Bazel 版本升级

- Bazel 优势

- Bazel 使用流程

- Bazel 构建流程

- Bazel 语法

- Output Directory Layout (输出目录布局)

- Action Graph (依赖图)

- Bazel 基础概念

- Bazel Tutorial: Build a C++ Project

- Common C++ Build Use Cases

- Build programs with Bazel

- Commands and Options

- C++ and Bazel

- Best Practices (C++)

- General Rules

- External dependencies overview

- Bazel Tutorial: Configure C++ Toolchains

- Workspace Rules

- Remote Caching - RC

- Remote Execution Overview - RE

- 如何分析构建耗时

- Starlark Language

- Sharing Variables

- 自定义扩展

- Creating a Macro

- Rules Tutorial

- 最佳实践

- 修改 bazel 输出目录使用 SSD 磁盘存储

- 在二进制中注入版本信息

- .bazelrc flags you should enable

- Fixing Bazel out-of-memory problems

- 生成 compile_commands.json 文件

- 对 cc_binary 禁止使用远程缓存

- 如何对使用远程缓存文件上传进行优化

- How to avoid ‘No space left’ on Bazel build?

- 条件编译

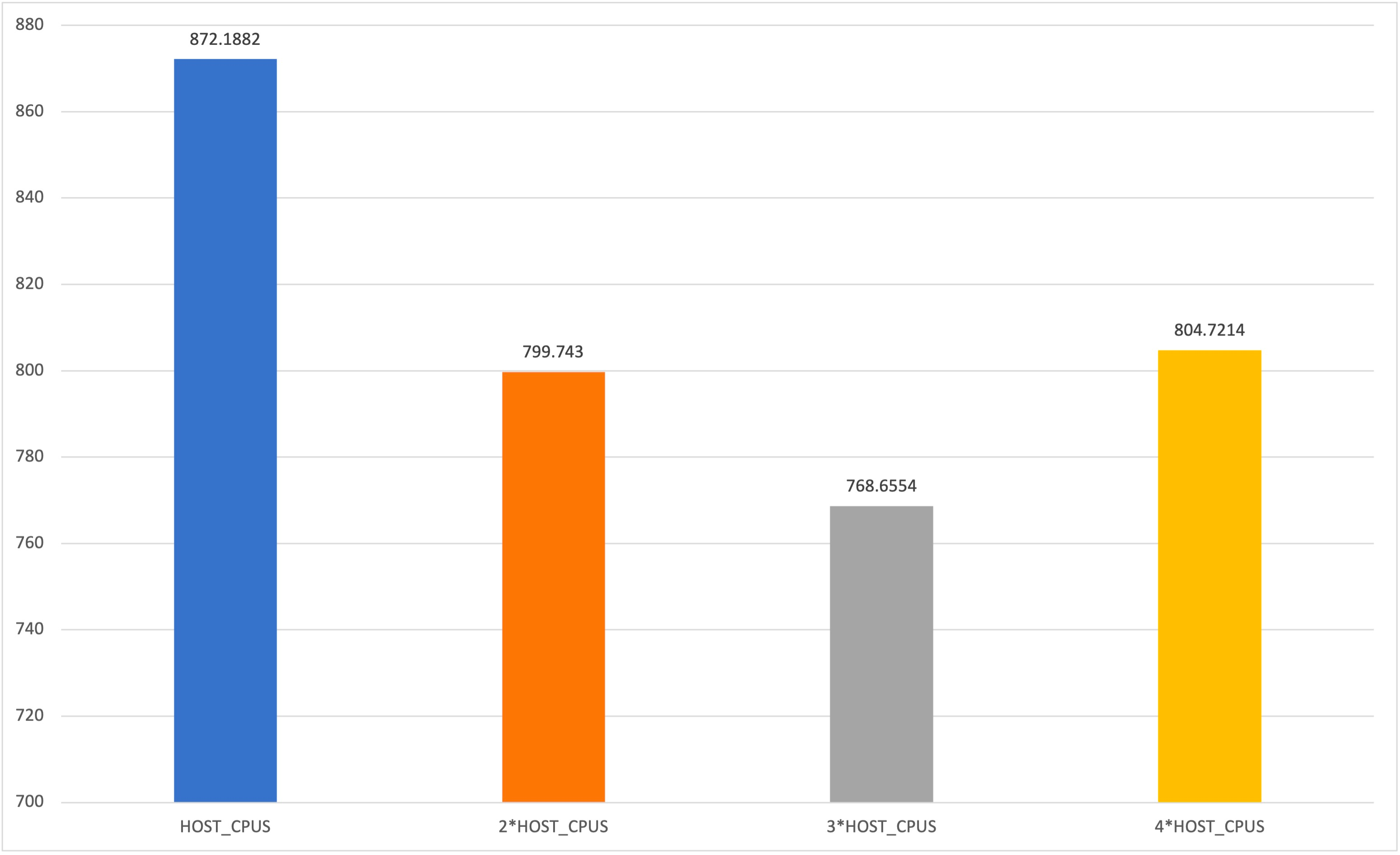

- 增加 bazel 并发度,提升构建效率 (–jobs)

- How do I install a project built with bazel?

- .bazelignore 忽略配置

- Recommended Rules

- bazel info

- bazel aquery

- bazel analyze-profile

- bazel print_action (查看有哪些 action)

- 构建性能

- Tools

- Protocol Buffers in Bazel

- Bazel 源码

- Bazel Release Model (版本发布说明)

- Tutorial

- Q&A

- Examples

- Refer

Bazel is an open-source build and test tool similar to

Make,Maven, andGradle. It uses a human-readable, high-level build language.Bazelsupports projects in multiple languages and builds outputs for multiple platforms.Bazelsupports large codebases across multiple repositories, and large numbers of users.

构建基础知识

观看一段简短的历史记录,了解基于工件的构建系统如何发展,以实现规模、速度和封闭性。

TL;DR (Bazel 构建需要完成的三件事)

- 修改头文件的路径,以

WORKSPACE所在目录为基准 - 编写

BUILD(对当前package软件包的描述)- 我是谁 (

name) - 我有什么 (

srcs/hdrs) - 我依赖什么 (

deps) - 其他选项 (

copts/linkopts/ …)

- 我是谁 (

- 解决链接问题 (依赖顺序)

Bazel 构建优化方案

- 使用远程缓存:Bazel 支持远程缓存,这可以显著提高构建速度

- 使用远程执行:Bazel 支持将构建和测试任务分发到远程执行器上

- 优化构建规则:优化 Bazel 的构建规则,确保没有不必要的依赖

- 使用增量构建:Bazel 支持增量构建,只构建发生变化的部分

- 使用工作空间缓存:Bazel 支持将构建结果缓存到本地磁盘

- 调整并行度:Bazel 支持配置并行构建的线程数

- 采用分层构建:将项目分解为多个模块,每个模块只依赖于其下游模块

- 使用 Bazel 的分析器:Bazel 提供了分析工具,可以帮助找到构建过程中的瓶颈

Bazel 安装 (CentOS 环境)

Bazel 安装说明,本文使用方式三。

方式一:安装包

yum install bazel4

方式二:源码编译

方式三:使用release版本

方式四:基于 Bazelisk 的安装

Bazelisk is a wrapper for Bazel written in Go. It automatically picks a good version of Bazel given your current working directory, downloads it from the official server (if required) and then transparently passes through all command-line arguments to the real Bazel binary. You can call it just like you would call Bazel.

sudo wget -O /usr/local/bin/bazel https://github.com/bazelbuild/bazelisk/releases/download/v1.17.0/bazelisk-linux-amd64

sudo chmod +x /usr/local/bin/bazel

完整的安装脚本:先检查本地是否有,没有则下载安装

#!/bin/bash

CUR_DIR=$(dirname $(readlink -f $0))

# Specify the Bazelisk version to install

BAZELISK_VERSION="1.17.0"

BAZELISK_DOWNLOAD_URL="https://github.com/bazelbuild/bazelisk/releases/download/v${BAZELISK_VERSION}/bazelisk-linux-amd64"

LOCAL_BAZELISK_FILE="$CUR_DIR/bazelisk-linux-amd64-1.17.0/bazelisk-linux-amd64"

# Check if Bazelisk is already installed

if command -v bazel &> /dev/null; then

echo "Bazelisk is already installed, version: $(bazel --version)"

else

echo "Installing Bazelisk version ${BAZELISK_VERSION}..."

if [[ -f "${LOCAL_BAZELISK_FILE}" ]]; then

echo "Using local Bazelisk file: ${LOCAL_BAZELISK_FILE}"

cp "${LOCAL_BAZELISK_FILE}" "bazelisk-linux-amd64"

elif wget -O "bazelisk-linux-amd64" --tries=1 "${BAZELISK_DOWNLOAD_URL}"; then

echo "Downloaded Bazelisk from ${BAZELISK_DOWNLOAD_URL}"

else

echo "Error: Could not download Bazelisk and local file not found"

exit 1

fi

# Move Bazelisk to the /usr/local/bin directory and make it executable

sudo mv "bazelisk-linux-amd64" /usr/local/bin/bazel

sudo chmod +x /usr/local/bin/bazel

echo "Bazelisk installation completed, version:"

echo "-----------------------------------------"

echo "$(bazel version)"

echo "-----------------------------------------"

fi

参考 How does Bazelisk know which Bazel version to run? 控制使用的 bazel 版本。

Bazel 版本升级

Bzlmod Migration Guide

Due to the shortcomings of WORKSPACE, Bzlmod is replacing the legacy WORKSPACE system. The WORKSPACE file is already disabled in Bazel 8 (late 2024) and will be removed in Bazel 9 (late 2025). This guide helps you migrate your project to Bzlmod and drop WORKSPACE for managing external dependencies.

Shortcomings of the WORKSPACE system

In the years since the WORKSPACE system was introduced, users have reported many pain points, including:

-

Bazel does not evaluate the

WORKSPACEfiles of any dependencies, so all transitive dependencies must be defined in theWORKSPACEfile of the main repo, in addition to direct dependencies. -

To work around this, projects have adopted the “deps.bzl” pattern, in which they define a macro which in turn defines multiple repos, and ask users to call this macro in their

WORKSPACEfiles.- This has its own problems: macros cannot

loadother.bzlfiles, so these projects have to define their transitive dependencies in this “deps” macro, or work around this issue by having the user call multiple layered “deps” macros. - Bazel evaluates the

WORKSPACEfile sequentially. Additionally, dependencies are specified usinghttp_archivewith URLs, without any version information. This means that there is no reliable way to perform version resolution in the case of diamond dependencies (A depends on B and C; B and C both depend on different versions of D).

- This has its own problems: macros cannot

Due to the shortcomings of WORKSPACE, Bzlmod is going to replace the legacy WORKSPACE system in future Bazel releases. Please read the Bzlmod migration guide on how to migrate to Bzlmod.

Why migrate to Bzlmod?

-

There are many advantages compared to the legacy

WORKSPACEsystem, which helps to ensure a healthy growth of the Bazel ecosystem. -

If your project is a dependency of other projects, migrating to

Bzlmodwill unblock their migration and make it easier for them to depend on your project. -

Migration to

Bzlmodis a necessary step in order to use future Bazel versions (mandatory(强制性的) in Bazel 9).

Bazel 优势

Bazel offers the following advantages:

- High-level build language. Bazel uses an abstract, human-readable language to describe the build properties of your project at a high semantical level. Unlike other tools, Bazel operates on the concepts of libraries, binaries, scripts, and data sets, shielding you from the complexity of writing individual calls to tools such as compilers and linkers.

- Bazel is fast and reliable. Bazel caches all previously done work and tracks changes to both file content and build commands. This way, Bazel knows when something needs to be rebuilt, and rebuilds only that. To further speed up your builds, you can set up your project to build in a highly parallel and incremental fashion.

- Bazel is multi-platform. Bazel runs on Linux, macOS, and Windows. Bazel can build binaries and deployable packages for multiple platforms, including desktop, server, and mobile, from the same project.

- Bazel scales. Bazel maintains agility(敏捷) while handling builds with

100k+source files. It works with multiple repositories and user bases in the tens of thousands. - Bazel is extensible. Many languages are supported, and you can extend Bazel to support any other language or framework.

- 多语言,可并行

- 保证构建结果准确性

- 支持多 CPU 架构

- C/S 架构,Memory / Local / Remote 三级缓存,构建速度快

- 全面接管编译目标间依赖关系,支持分布式远程构建

- 全面追踪构建详情

一些测试结论:

bazel默认会限制并发度到其估计的机器性能上限,实际使用需要通过--local_cpu_resources=9999999等参数绕过这一限制- 已知(部分版本的)bazel 在并发度过高(如

-j320)下,bazel 自身性能存在瓶颈。这具体表现为机器空闲但不会启动更多编译任务,同时 bazel 自身 CPU(400~500%)、内存(几G)占用很高。 - 如果机器资源充足且对并发度有较高要求(几百并发),可以考虑使用其他构建系统构建。

Bazel 使用流程

To build or test a project with Bazel, you typically do the following:

- Set up Bazel. Download and install Bazel.

- Set up a project workspace, which is a directory where Bazel looks for build inputs and

BUILDfiles, and where it stores build outputs. - Write a BUILD file, which tells Bazel what to build and how to build it.

- You write your

BUILDfile by declaring build targets using Starlark, a domain-specific language. (See example here.) - A build target specifies a set of input artifacts that Bazel will build plus their dependencies, the build rule Bazel will use to build it, and options that configure the build rule.

- A build rule specifies the build tools Bazel will use, such as compilers and linkers, and their configurations. Bazel ships with a number of build rules covering the most common artifact types in the supported languages on supported platforms.

- You write your

- Run Bazel from the command line. Bazel places your outputs within the workspace.

In addition to building, you can also use Bazel to run tests and query the build to trace dependencies in your code.

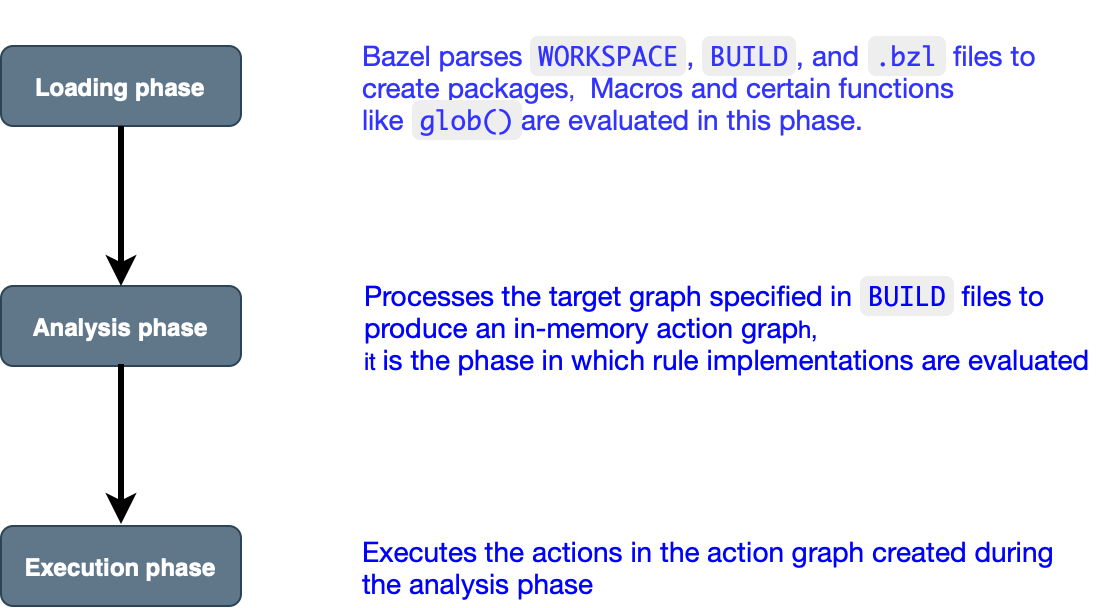

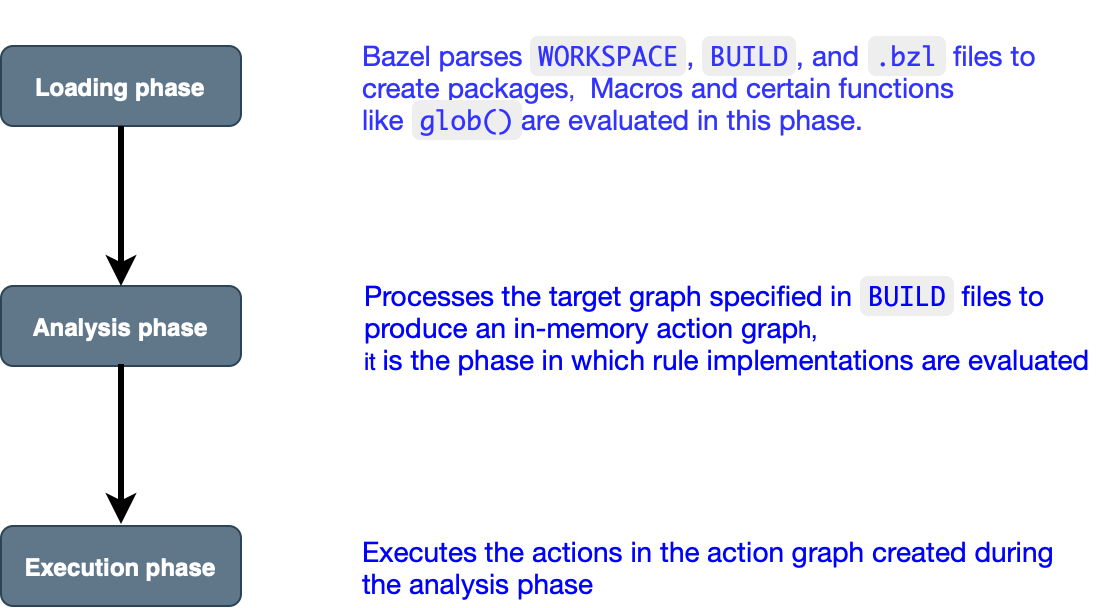

Bazel 构建流程

Bazel 构建分为三个阶段:Loading, Analysising and Executing

When running a build or a test, Bazel does the following:

- Loads the

BUILDfiles relevant to the target. - Analyzes the inputs and their dependencies, applies the specified build rules, and produces an action graph.

- Executes the build actions on the inputs until the final build outputs are produced.

Since all previous build work is cached, Bazel can identify and reuse cached artifacts and only rebuild or retest what’s changed. To further enforce correctness, you can set up Bazel to run builds and tests hermetically through sandboxing, minimizing skew and maximizing reproducibility.

下面针对这三个过程进行详细解释。

Loads

Bazel 在这个阶段会加载 WORKSPACE 和 BUILD,同时会加载相关的 .bzl 文件。这些文件可以来自本地,也可以来自 git_repository 或者 github 上面的其他第三方包。加载完毕之后,如果有macro 的定义,会处理相关 macro,替换成真正的 rules。Bazel 加载所有需要的文件完毕之后,下次重新构建就可以复用这些文件,而无须重复加载。

总结:在此阶段结束后,Bazel 已经形成了一个 target dependency 的体系,同时所有 target 所需要的文件都加载成功,target 分析成功,所有 macro 都展开成了 rules,并且都缓存到了内存中,下次重新运行规则,不需要重新加载文件、分析这些依赖关系。

Analyzes

分析阶段主要为执行这些函数,生成一个静态有向图Action Direct acyclic Graph,这个图表示需要构建的目标、目标之间的关系,以及为了构建目标需要执行的动作。每一个函数都生成静态图中的一个结点,根据结点中定义的 label 和其他信息,构建结点之间的依赖关系。另外 Bazel 会缓存 Action Graph,对于没有变化的构建,会直接从缓存中读取,也就是增量构建。

在这个过程中,主要是执行规则,生成 Action,并未真正开始执行任何读写 inputs ouputs 等操作。通过 bazel query –output graph,可以查看生成的 Action Graph 图形。

总结:在此阶段结束后,所有需要用到的规则都会被执行一次,Bazel 已经形成了一个 action dependency 体系,存放在内存中。

Executes

主要是根据 Analyzes 阶段生成的 Action Direct Acyclic Graph,结合它们的依赖关系进行调度执行。对于不依赖别人的对象可直接执行,而依赖其他 Action 的就等其他执行好了才可以继续。也就是在这个阶段才会开始真正 compile link 项目,输出各种文件,执行各种 IO 操作。

总结:所有需要用到的 action 均执行完毕。

Bazel 语法

$bazel help target-syntax

[bazel release 6.2.1]

Target pattern syntax

=====================

The BUILD file label syntax is used to specify a single target. Target

patterns generalize this syntax to sets of targets, and also support

working-directory-relative forms, recursion, subtraction and filtering.

Examples:

Specifying a single target:

//foo/bar:wiz The single target '//foo/bar:wiz'.

foo/bar/wiz Equivalent to:

'//foo/bar/wiz:wiz' if foo/bar/wiz is a package,

'//foo/bar:wiz' if foo/bar is a package,

'//foo:bar/wiz' otherwise.

//foo/bar Equivalent to '//foo/bar:bar'.

Specifying all rules in a package:

//foo/bar:all Matches all rules in package 'foo/bar'.

Specifying all rules recursively beneath a package:

//foo/...:all Matches all rules in all packages beneath directory 'foo'.

//foo/... (ditto)

By default, directory symlinks are followed when performing this recursive traversal, except

those that point to under the output base (for example, the convenience symlinks that are created

in the root directory of the workspace) But we understand that your workspace may intentionally

contain directories with weird symlink structures that you don't want consumed. As such, if a

directory has a file named

'DONT_FOLLOW_SYMLINKS_WHEN_TRAVERSING_THIS_DIRECTORY_VIA_A_RECURSIVE_TARGET_PATTERN'

then symlinks in that directory won't be followed when evaluating recursive

target patterns.

Working-directory relative forms: (assume cwd = 'workspace/foo')

Target patterns which do not begin with '//' are taken relative to

the working directory. Patterns which begin with '//' are always

absolute.

...:all Equivalent to '//foo/...:all'.

... (ditto)

bar/...:all Equivalent to '//foo/bar/...:all'.

bar/... (ditto)

bar:wiz Equivalent to '//foo/bar:wiz'.

:foo Equivalent to '//foo:foo'.

bar Equivalent to '//foo/bar:bar'.

foo/bar Equivalent to '//foo/foo/bar:bar'.

bar:all Equivalent to '//foo/bar:all'.

:all Equivalent to '//foo:all'.

Summary of target wildcards:

:all, Match all rules in the specified packages.

:*, :all-targets Match all targets (rules and files) in the specified

packages, including .par and _deploy.jar files.

Subtractive patterns:

Target patterns may be preceded by '-', meaning they should be

subtracted from the set of targets accumulated by preceding

patterns. (Note that this means order matters.) For example:

% bazel build -- foo/... -foo/contrib/...

builds everything in 'foo', except 'contrib'. In case a target not

under 'contrib' depends on something under 'contrib' though, in order to

build the former bazel has to build the latter too. As usual, the '--' is

required to prevent '-f' from being interpreted as an option.

When running the test command, test suite expansion is applied to each target

pattern in sequence as the set of targets is evaluated. This means that

individual tests from a test suite can be excluded by a later target pattern.

It also means that an exclusion target pattern which matches a test suite will

exclude all tests which that test suite references. (Targets that would be

matched by the list of target patterns without any test suite expansion are

also built unless --build_tests_only is set.)

(Use 'help --long' for full details or --short to just enumerate options.)

Output Directory Layout (输出目录布局)

Current layout (当前布局)

The solution that’s currently implemented:

-

Bazel must be invoked from a directory containing a

WORKSPACEfile (the “workspace directory”), or a subdirectory thereof. It reports an error if it is not. -

The

outputRootdirectory defaults to~/.cache/bazelon Linux,/private/var/tmpon macOS, and on Windows it defaults to%HOME%if set, else%USERPROFILE%if set, else the result of callingSHGetKnownFolderPath()with theFOLDERID_Profileflag set. If the environment variable$TEST_TMPDIRis set, as in a test of Bazel itself, then that value overrides the default. -

The Bazel user’s build state is located beneath

outputRoot/_bazel_$USER. This is called the outputUserRoot directory. -

Beneath the outputUserRoot directory there is an

installdirectory, and in it is aninstallBasedirectory whose name is the MD5 hash of the Bazel installation manifest. -

Beneath the outputUserRoot directory, an outputBase directory is also created whose name is the MD5 hash of the path name of the workspace directory. So, for example, if Bazel is running in the workspace directory

/home/user/src/my-project(or in a directory symlinked to that one), then an output base directory is created called:/home/user/.cache/bazel/_bazel_user/7ffd56a6e4cb724ea575aba15733d113. You can also runecho -n $(pwd) | md5sumin a Bazel workspace to get the MD5. -

You can use Bazel’s

--output_basestartup option to override the default output base directory. For example,bazel --output_base=/tmp/bazel/output build x/y:z. -

You can also use Bazel’s

--output_user_rootstartup option to override the default install base and output base directories. For example:bazel --output_user_root=/tmp/bazel build x/y:z.

The symlinks for “bazel-<workspace-name>”, “bazel-out”, “bazel-testlogs”, and “bazel-bin” are put in the workspace directory; these symlinks point to some directories inside a target-specific directory inside the output directory. These symlinks are only for the user’s convenience, as Bazel itself does not use them. Also, this is done only if the workspace directory is writable.

--output_base 和 --output_user_root 都是 Bazel 配置选项,用于设置 Bazel 缓存和输出文件的存储位置。它们之间的主要区别在于它们影响的目录结构层次。

--output_base:此选项设置 Bazel 的输出基目录。Bazel 会在此目录下创建一个名为 execroot 的子目录,用于存储构建过程中的所有文件,包括缓存、构建输出、日志等。此选项允许您为所有 Bazel 项目设置一个统一的输出基目录。例如,如果您设置 --output_base=/data/cache/bazel,那么所有项目的构建输出和缓存将存储在 /data/cache/bazel/execroot 目录下。

--output_user_root:此选项设置 Bazel 的用户根目录。Bazel 会在此目录下为每个工作区创建一个子目录,用于存储与特定工作区相关的缓存和输出文件。例如,如果您设置 --output_user_root=/dev/shm/bazel_cache,那么每个工作区的构建输出和缓存将存储在 /dev/shm/bazel_cache/<workspace_name> 目录下。

总之,--output_base 设置了一个全局的输出基目录,适用于所有 Bazel 项目,而 --output_user_root 设置了一个用户根目录,允许为每个工作区创建单独的缓存和输出目录。在大多数情况下,设置 --output_user_root 更具灵活性,因为它允许您为不同的工作区分配不同的缓存和输出目录。然而,如果您希望为所有项目设置一个统一的缓存和输出位置,可以选择使用 --output_base。

Layout diagram (布局示意图)

The directories are laid out as follows:

<workspace-name>/ <== The workspace directory

bazel-my-project => <...my-project> <== Symlink to execRoot

bazel-out => <...bin> <== Convenience symlink to outputPath

bazel-bin => <...bin> <== Convenience symlink to most recent written bin dir $(BINDIR)

bazel-testlogs => <...testlogs> <== Convenience symlink to the test logs directory

/home/user/.cache/bazel/ <== Root for all Bazel output on a machine: outputRoot

_bazel_$USER/ <== Top level directory for a given user depends on the user name:

outputUserRoot

install/

fba9a2c87ee9589d72889caf082f1029/ <== Hash of the Bazel install manifest: installBase

_embedded_binaries/ <== Contains binaries and scripts unpacked from the data section of

the bazel executable on first run (such as helper scripts and the

main Java file BazelServer_deploy.jar)

7ffd56a6e4cb724ea575aba15733d113/ <== Hash of the client's workspace directory (such as

/home/user/src/my-project): outputBase

action_cache/ <== Action cache directory hierarchy

This contains the persistent record of the file

metadata (timestamps, and perhaps eventually also MD5

sums) used by the FilesystemValueChecker.

command.log <== A copy of the stdout/stderr output from the most

recent bazel command.

external/ <== The directory that remote repositories are

downloaded/symlinked into.

server/ <== The Bazel server puts all server-related files (such

as socket file, logs, etc) here.

jvm.out <== The debugging output for the server.

execroot/ <== The working directory for all actions. For special

cases such as sandboxing and remote execution, the

actions run in a directory that mimics execroot.

Implementation details, such as where the directories

are created, are intentionally hidden from the action.

Every action can access its inputs and outputs relative

to the execroot directory.

<workspace-name>/ <== Working tree for the Bazel build & root of symlink forest: execRoot

_bin/ <== Helper tools are linked from or copied to here.

bazel-out/ <== All actual output of the build is under here: outputPath

_tmp/actions/ <== Action output directory. This contains a file with the

stdout/stderr for every action from the most recent

bazel run that produced output.

local_linux-fastbuild/ <== one subdirectory per unique target BuildConfiguration instance;

this is currently encoded

bin/ <== Bazel outputs binaries for target configuration here: $(BINDIR)

foo/bar/_objs/baz/ <== Object files for a cc_* rule named //foo/bar:baz

foo/bar/baz1.o <== Object files from source //foo/bar:baz1.cc

other_package/other.o <== Object files from source //other_package:other.cc

foo/bar/baz <== foo/bar/baz might be the artifact generated by a cc_binary named

//foo/bar:baz

foo/bar/baz.runfiles/ <== The runfiles symlink farm for the //foo/bar:baz executable.

MANIFEST

<workspace-name>/

...

genfiles/ <== Bazel puts generated source for the target configuration here:

$(GENDIR)

foo/bar.h such as foo/bar.h might be a headerfile generated by //foo:bargen

testlogs/ <== Bazel internal test runner puts test log files here

foo/bartest.log such as foo/bar.log might be an output of the //foo:bartest test with

foo/bartest.status foo/bartest.status containing exit status of the test (such as

PASSED or FAILED (Exit 1), etc)

include/ <== a tree with include symlinks, generated as needed. The

bazel-include symlinks point to here. This is used for

linkstamp stuff, etc.

host/ <== BuildConfiguration for build host (user's workstation), for

building prerequisite tools, that will be used in later stages

of the build (ex: Protocol Compiler)

<packages>/ <== Packages referenced in the build appear as if under a regular workspace

The layout of the *.runfiles directories is documented in more detail in the places pointed to by RunfilesSupport.

bazel clean

bazel clean does an rm -rf on the outputPath and the action_cache directory. It also removes the workspace symlinks. The –expunge option will clean the entire outputBase. (bazel clean 对 outputPath 和 action_cache 目录执行 rm -rf。还会移除工作区符号链接。–expunge 选项将清理整个 outputBase。)

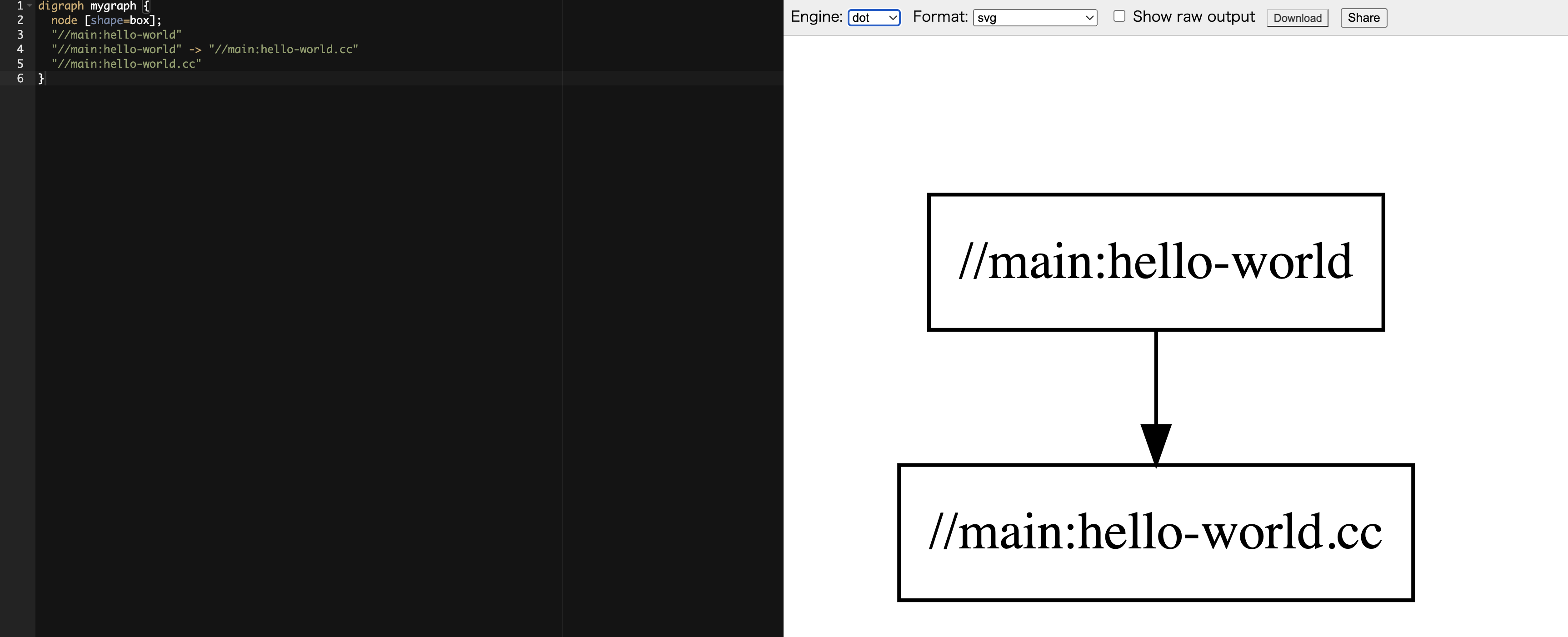

Action Graph (依赖图)

The action graph represents the build artifacts, the relationships between them, and the build actions that Bazel will perform. Thanks to this graph, Bazel can track changes to file content as well as changes to actions, such as build or test commands, and know what build work has previously been done. The graph also enables you to easily trace dependencies in your code.

通过 bazel query 输出 graphviz 格式数据,然后在 GraphvizOnline 查看依赖图。

~/github/bazelbuild/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage1$ bazel query --nohost_deps --noimplicit_deps 'deps(//main:hello-world)' --output graph

digraph mygraph {

node [shape=box];

"//main:hello-world"

"//main:hello-world" -> "//main:hello-world.cc"

"//main:hello-world.cc"

}

Loading: 0 packages loaded

完整的依赖图:

~/github/bazelbuild/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage1$bazel query 'deps(//main:hello-world)' --output graph

digraph mygraph {

node [shape=box];

"//main:hello-world"

"//main:hello-world" -> "//main:hello-world.cc"

"//main:hello-world" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:malloc"

"//main:hello-world" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:current_cc_toolchain"

"//main:hello-world" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser"

"//main:hello-world" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:toolchain_type"

"//main:hello-world.cc"

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser"

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser_windows"

[label="@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows"];

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser" -> "@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows"

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:no_op.bat"

[label="//conditions:default"];

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:no_op.bat"

"@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows"

"@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows" -> "@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows_x64_constraint\n@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows_arm64_constraint"

[label="//conditions:default@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows_arm64_constraint"];

"@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows_x64_constraint\n@bazel_tools//src/conditions:host_windows_arm64_constraint"

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser_windows"

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser_windows" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser.exe\n@bazel_tools//src/conditions:remote"

[label="//conditions:default"];

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser_windows" -> "@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser"

[label="@bazel_tools//src/conditions:remote"];

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser" -> "@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser_main.cc"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser" -> "@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser_lib"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:malloc"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:current_cc_toolchain"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:toolchain_type"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:toolchain_type"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:malloc"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:malloc" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:grep-includes"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:malloc" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:current_cc_toolchain"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser_lib"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser_lib" -> "@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser.cc\n@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser.h"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser_lib" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:grep-includes"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser_lib" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:current_cc_toolchain"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:current_cc_toolchain"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:current_cc_toolchain" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:toolchain"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:toolchain"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:toolchain" -> "@local_config_cc//:toolchain"

"@local_config_cc//:toolchain"

"@local_config_cc//:toolchain" -> "@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-k8"

"@local_config_cc//:toolchain" -> "@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-armeabi-v7a"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-armeabi-v7a"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-armeabi-v7a" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/build_defs/cc/whitelists/parse_headers_and_layering_check:disabling_parse_headers_and_layering_check_allowed\n@local_config_cc//:empty\n@bazel_tools//tools/build_defs/cc/whitelists/starlark_hdrs_check:loose_header_check_allowed_in_toolchain"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-armeabi-v7a" -> "@local_config_cc//:stub_armeabi-v7a"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-armeabi-v7a" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:link_dynamic_library"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-armeabi-v7a" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:interface_library_builder"

"@local_config_cc//:stub_armeabi-v7a"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-k8"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-k8" -> "@local_config_cc//:compiler_deps"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-k8" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/build_defs/cc/whitelists/parse_headers_and_layering_check:disabling_parse_headers_and_layering_check_allowed\n@local_config_cc//:empty\n@bazel_tools//tools/build_defs/cc/whitelists/starlark_hdrs_check:loose_header_check_allowed_in_toolchain"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-k8" -> "@local_config_cc//:local"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-k8" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:interface_library_builder"

"@local_config_cc//:cc-compiler-k8" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:link_dynamic_library"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:link_dynamic_library"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:link_dynamic_library" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:link_dynamic_library.sh"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:link_dynamic_library.sh"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:interface_library_builder"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:interface_library_builder" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:build_interface_so"

"@local_config_cc//:local"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:grep-includes"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:grep-includes" -> "@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:grep-includes.sh"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:grep-includes.sh"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser.cc\n@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser.h"

"@bazel_tools//third_party/def_parser:def_parser_main.cc"

"@bazel_tools//tools/def_parser:def_parser.exe\n@bazel_tools//src/conditions:remote"

"@local_config_cc//:compiler_deps"

"@local_config_cc//:compiler_deps" -> "@local_config_cc//:builtin_include_directory_paths"

"@local_config_cc//:builtin_include_directory_paths"

"@bazel_tools//tools/build_defs/cc/whitelists/parse_headers_and_layering_check:disabling_parse_headers_and_layering_check_allowed\n@local_config_cc//:empty\n@bazel_tools//tools/build_defs/cc/whitelists/starlark_hdrs_check:loose_header_check_allowed_in_toolchain"

"@bazel_tools//tools/cpp:build_interface_so"

}

Loading: 0 packages loaded

也可安装 xdot 直接显示:bazel query --nohost_deps --noimplicit_deps 'deps(//main:hello-world)' --output graph | xdot

~/tools/xdot/xdot-1.2$./setup.py install

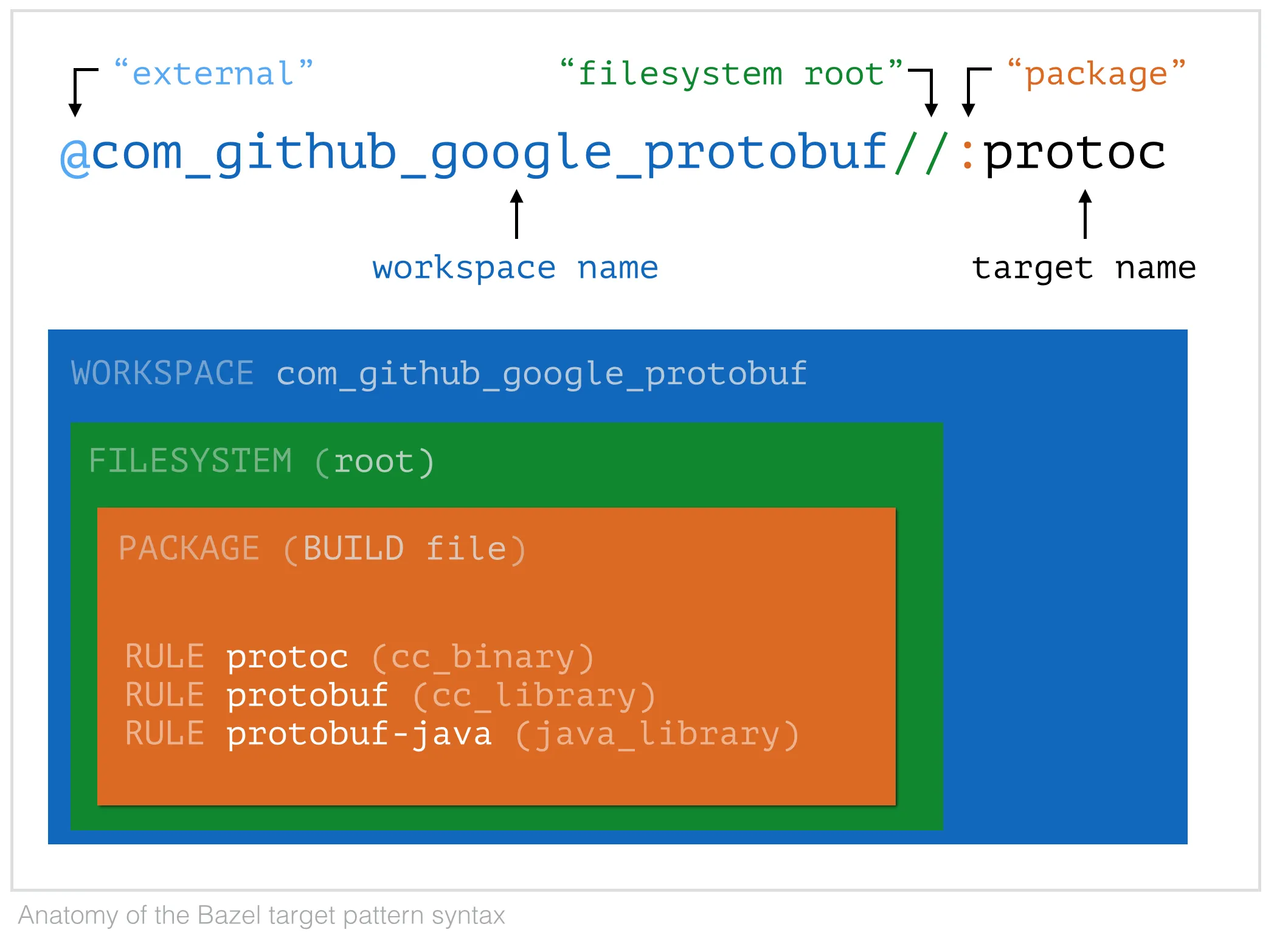

Bazel 基础概念

了解源代码布局,BUILD 文件语法以及规则和依赖项类型等基本概念。

Workspaces, packages, and targets / 中文版

Bazel 会根据名为“工作区”的目录树整理的源代码构建软件。工作区中的源文件以嵌套的软件包层次结构进行组织,其中每个软件包都是一个包含一组相关源文件和一个 BUILD 文件的目录。BUILD 文件指定可以从源代码构建哪些软件输出。

Workspace (工作空间位于根目录)

A workspace is a directory tree on your filesystem that contains the source files for the software you want to build. Each workspace has a text file named WORKSPACE which may be empty, or may contain references to external dependencies required to build the outputs.

Directories containing a file called WORKSPACE are considered the root of a workspace. Therefore, Bazel ignores any directory trees in a workspace rooted at a subdirectory containing a WORKSPACE file, as they form another workspace.

Bazel also supports WORKSPACE.bazel file as an alias of WORKSPACE file. If both files exist, WORKSPACE.bazel is used.

Repositories

Code is organized in repositories. The directory containing the WORKSPACE file is the root of the main repository, also called @. Other, (external) repositories are defined in the WORKSPACE file using workspace rules, or generated from modules and extensions in the Bzlmod system. See external dependencies overview for more information.

The workspace rules bundled with Bazel are documented in the Workspace Rules section in the Build Encyclopedia and the documentation on embedded Starlark repository rules.

As external repositories are repositories themselves, they often contain a WORKSPACE file as well. However, these additional WORKSPACE files are ignored by Bazel. In particular, repositories depended upon transitively are not added automatically.

Packages (包含 BUILD 文件的目录称为包)

The primary unit of code organization in a repository is the package. A package is a collection of related files and a specification of how they can be used to produce output artifacts.

A package is defined as a directory containing a BUILD file named either BUILD or BUILD.bazel. A package includes all files in its directory, plus all subdirectories beneath it, except those which themselves contain a BUILD file. From this definition, no file or directory may be a part of two different packages.

For example, in the following directory tree there are two packages, my/app, and the subpackage my/app/tests. Note that my/app/data is not a package, but a directory belonging to package my/app.

src/my/app/BUILD

src/my/app/app.cc

src/my/app/data/input.txt

src/my/app/tests/BUILD

src/my/app/tests/test.cc

Targets (BUILD 中的每个构建规则称为目标)

A package is a container of targets, which are defined in the package’s BUILD file. Most targets are one of two principal kinds, files and rules.

Files are further divided into two kinds. Source files are usually written by the efforts of people, and checked in to the repository. Generated files, sometimes called derived files or output files, are not checked in, but are generated from source files.

The second kind of target is declared with a rule. Each rule instance specifies the relationship between a set of input and a set of output files. The inputs to a rule may be source files, but they also may be the outputs of other rules.

Whether the input to a rule is a source file or a generated file is in most cases immaterial (不重要的); what matters is only the contents of that file. This fact makes it easy to replace a complex source file with a generated file produced by a rule, such as happens when the burden of manually maintaining a highly structured file becomes too tiresome, and someone writes a program to derive it. No change is required to the consumers of that file. Conversely, a generated file may easily be replaced by a source file with only local changes.

The inputs to a rule may also include other rules. The precise meaning of such relationships is often quite complex and language- or rule-dependent, but intuitively it is simple: a C++ library rule A might have another C++ library rule B for an input. The effect of this dependency is that B’s header files are available to A during compilation, B’s symbols are available to A during linking, and B’s runtime data is available to A during execution.

An invariant of all rules is that the files generated by a rule always belong to the same package as the rule itself; it is not possible to generate files into another package. It is not uncommon for a rule’s inputs to come from another package, though.

Package groups are sets of packages whose purpose is to limit accessibility of certain rules. Package groups are defined by the package_group function. They have three properties: the list of packages they contain, their name, and other package groups they include. The only allowed ways to refer to them are from the visibility attribute of rules or from the default_visibility attribute of the package function; they do not generate or consume files. For more information, refer to the package_group documentation.

Labels

All targets belong to exactly one package. The name of a target is called its label. Every label uniquely identifies a target. A typical label in canonical form looks like:

@myrepo//my/app/main:app_binary

BUILD files

The previous sections described packages, targets and labels, and the build dependency graph abstractly. This section describes the concrete syntax used to define a package.

By definition, every package contains a BUILD file, which is a short program.

Note: The BUILD file can be named either BUILD or BUILD.bazel. If both files exist, BUILD.bazel takes precedence over BUILD. For simplicity’s sake, the documentation refers to these files simply as BUILD files.

BUILD files are evaluated using an imperative language, Starlark.

Loading an extension

Bazel extensions are files ending in .bzl. Use the load statement to import a symbol from an extension.

load("//foo/bar:file.bzl", "some_library")

This code loads the file foo/bar/file.bzl and adds the some_library symbol to the environment. This can be used to load new rules, functions, or constants (for example, a string or a list). Multiple symbols can be imported by using additional arguments to the call to load. Arguments must be string literals (no variable) and load statements must appear at top-level — they cannot be in a function body.

The first argument of load is a label identifying a .bzl file. If it’s a relative label, it is resolved with respect to the package (not directory) containing the current bzl file. Relative labels in load statements should use a leading :.

In a .bzl file, symbols starting with _ are not exported and cannot be loaded from another file.

You can use load visibility to restrict who may load a .bzl file.

Types of build rules

The majority of build rules come in families, grouped together by language. For example, cc_binary, cc_library and cc_test are the build rules for C++ binaries, libraries, and tests, respectively. Other languages use the same naming scheme, with a different prefix, such as java_* for Java. Some of these functions are documented in the Build Encyclopedia, but it is possible for anyone to create new rules.

*_binary

*_binary rules build executable programs in a given language. After a build, the executable will reside in the build tool’s binary output tree at the corresponding name for the rule’s label, so //my:program would appear at (for example) $(BINDIR)/my/program.

In some languages, such rules also create a runfiles directory containing all the files mentioned in a data attribute belonging to the rule, or any rule in its transitive closure of dependencies; this set of files is gathered together in one place for ease of deployment to production.

*_test

*_test rules are a specialization of a *_binary rule, used for automated testing. Tests are simply programs that return zero on success.

Like binaries, tests also have runfiles trees, and the files beneath it are the only files that a test may legitimately open at runtime. For example, a program cc_test(name='x', data=['//foo:bar']) may open and read $TEST_SRCDIR/workspace/foo/bar during execution. (Each programming language has its own utility function for accessing the value of $TEST_SRCDIR, but they are all equivalent to using the environment variable directly.) Failure to observe the rule will cause the test to fail when it is executed on a remote testing host.

*_library

*_library rules specify separately-compiled modules in the given programming language. Libraries can depend on other libraries, and binaries and tests can depend on libraries, with the expected separate-compilation behavior.

Dependencies

A target A depends upon a target B if B is needed by A at build or execution time. The depends upon relation induces a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG 有向无环图) over targets, and it is called a dependency graph.

A target’s direct dependencies (直接依赖) are those other targets reachable by a path of length 1 in the dependency graph. A target’s transitive dependencies (间接依赖) are those targets upon which it depends via a path of any length through the graph.

In fact, in the context of builds, there are two dependency graphs, the graph of actual dependencies (实际依赖图) and the graph of declared dependencies (声明依赖图). Most of the time, the two graphs are so similar that this distinction need not be made, but it is useful for the discussion below.

Actual and declared dependencies

A target X is actually dependent on target Y if Y must be present, built, and up-to-date in order for X to be built correctly. Built could mean generated, processed, compiled, linked, archived, compressed, executed, or any of the other kinds of tasks that routinely occur during a build.

Types of dependencies (依赖类型)

Most build rules have three attributes for specifying different kinds of generic dependencies: srcs, deps and data. These are explained below. For more details, see Attributes common to all rules.

Many rules also have additional attributes for rule-specific kinds of dependencies, for example, compiler or resources. These are detailed in the Build Encyclopedia.

srcs dependencies

Files consumed directly by the rule or rules that output source files.

deps dependencies

Rule pointing to separately-compiled modules providing header files, symbols, libraries, data, etc.

data dependencies

A build target might need some data files to run correctly. These data files aren’t source code: they don’t affect how the target is built. For example, a unit test might compare a function’s output to the contents of a file. When you build the unit test you don’t need the file, but you do need it when you run the test. The same applies to tools that are launched during execution.

Visibility

This page covers Bazel’s two visibility systems: target visibility and load visibility.

Bazel Tutorial: Build a C++ Project

Start by installing Bazel, if you haven’t already. This tutorial uses Git for source control, so for best results install Git as well.

Next, retrieve the sample project from Bazel’s GitHub repository by running the following in your command-line tool of choice:

git clone https://github.com/bazelbuild/examples

The sample project for this tutorial is in the examples/cpp-tutorial directory.

Take a look below at how it’s structured:

There are three sets of files, each set representing a stage in this tutorial.

- In the first stage, you will build a single target residing in a single package.

- In the second stage, you will build both a binary and a library from a single package.

- In the third and final stage, you will build a project with multiple packages and build it with multiple targets.

~/github/examples$tree cpp-tutorial/

cpp-tutorial/

├── README.md

├── stage1

│ ├── main

│ │ ├── BUILD

│ │ └── hello-world.cc

│ ├── README.md

│ └── WORKSPACE

├── stage2

│ ├── main

│ │ ├── BUILD

│ │ ├── hello-greet.cc

│ │ ├── hello-greet.h

│ │ └── hello-world.cc

│ ├── README.md

│ └── WORKSPACE

└── stage3

├── lib

│ ├── BUILD

│ ├── hello-time.cc

│ └── hello-time.h

├── main

│ ├── BUILD

│ ├── hello-greet.cc

│ ├── hello-greet.h

│ └── hello-world.cc

├── README.md

└── WORKSPACE

7 directories, 20 files

Set up the workspace

Before you can build a project, you need to set up its workspace. A workspace is a directory that holds your project’s source files and Bazel’s build outputs. It also contains these significant files:

- The

WORKSPACEfile , which identifies the directory and its contents as a Bazel workspace and lives at the root of the project’s directory structure. - One or more

BUILDfiles, which tell Bazel how to build different parts of the project. A directory within the workspace that contains aBUILDfile is a package. (More on packages later in this tutorial.)

In future projects, to designate a directory as a Bazel workspace, create an empty file named WORKSPACE in that directory. For the purposes of this tutorial, a WORKSPACE file is already present in each stage.

NOTE: When Bazel builds the project, all inputs must be in the same workspace. Files residing in different workspaces are independent of one another unless linked. More detailed information about workspace rules can be found in this guide.

Understand the BUILD file

A BUILD file contains several different types of instructions for Bazel. Each BUILD file requires at least one rule as a set of instructions, which tells Bazel how to build the desired outputs, such as executable binaries or libraries. Each instance of a build rule in the BUILD file is called a target and points to a specific set of source files and dependencies. A target can also point to other targets.

Take a look at the BUILD file in the cpp-tutorial/stage1/main directory:

cc_binary(

name = "hello-world",

srcs = ["hello-world.cc"],

)

In our example, the hello-world target instantiates Bazel’s built-in cc_binary rule. The rule tells Bazel to build a self-contained executable binary from the hello-world.cc source file with no dependencies.

Now you are familiar with some key terms, and what they mean in the context of this project and Bazel in general. In the next section, you will build and test Stage 1 of the project.

Stage 1: single target, single package

It’s time to build the first part of the project. For a visual reference, the structure of the Stage 1 section of the project is:

examples

└── cpp-tutorial

└──stage1

├── main

│ ├── BUILD

│ └── hello-world.cc

└── WORKSPACE

Run the following to move to the cpp-tutorial/stage1 directory:

$ cd ../cpp-tutorial/stage1

Next, run:

$ bazel build //main:hello-world

In the target label, the //main: part is the location of the BUILD file relative to the root of the workspace, and hello-world is the target name in the BUILD file.

~/github/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage1/main$cat BUILD

load("@rules_cc//cc:defs.bzl", "cc_binary")

cc_binary(

name = "hello-world",

srcs = ["hello-world.cc"],

)

// ~/github/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage1/main$cat hello-world.cc

#include <ctime>

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

std::string get_greet(const std::string& who) {

return "Hello " + who;

}

void print_localtime() {

std::time_t result = std::time(nullptr);

std::cout << std::asctime(std::localtime(&result));

}

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

std::string who = "world";

if (argc > 1) {

who = argv[1];

}

std::cout << get_greet(who) << std::endl;

print_localtime();

return 0;

}

Bazel produces something that looks like this:

~/github/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage1$bazel build //main:hello-world

WARNING: Ignoring JAVA_HOME, because it must point to a JDK, not a JRE.

Starting local Bazel server and connecting to it...

INFO: Analyzed target //main:hello-world (34 packages loaded, 149 targets configured).

INFO: Found 1 target...

Target //main:hello-world up-to-date:

bazel-bin/main/hello-world

INFO: Elapsed time: 7.903s, Critical Path: 0.62s

INFO: 6 processes: 4 internal, 2 processwrapper-sandbox.

INFO: Build completed successfully, 6 total actions

You just built your first Bazel target. Bazel places build outputs in the bazel-bin directory at the root of the workspace.

~/github/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage1$tree

.

├── bazel-bin -> /data/home/gerryyang/.cache/bazel/_bazel_gerryyang/0fa77b61e0ee4749e8c3bda193f05839/execroot/__main__/bazel-out/k8-fastbuild/bin

├── bazel-out -> /data/home/gerryyang/.cache/bazel/_bazel_gerryyang/0fa77b61e0ee4749e8c3bda193f05839/execroot/__main__/bazel-out

├── bazel-stage1 -> /data/home/gerryyang/.cache/bazel/_bazel_gerryyang/0fa77b61e0ee4749e8c3bda193f05839/execroot/__main__

├── bazel-testlogs -> /data/home/gerryyang/.cache/bazel/_bazel_gerryyang/0fa77b61e0ee4749e8c3bda193f05839/execroot/__main__/bazel-out/k8-fastbuild/testlogs

├── main

│ ├── BUILD

│ └── hello-world.cc

├── README.md

└── WORKSPACE

5 directories, 4 files

~/github/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage1/bazel-bin$tree

.

└── main

├── hello-world

├── hello-world-2.params

├── hello-world.runfiles

│ ├── __main__

│ │ └── main

│ │ └── hello-world -> /data/home/gerryyang/.cache/bazel/_bazel_gerryyang/0fa77b61e0ee4749e8c3bda193f05839/execroot/__main__/bazel-out/k8-fastbuild/bin/main/hello-world

│ └── MANIFEST

├── hello-world.runfiles_manifest

└── _objs

└── hello-world

├── hello-world.pic.d

└── hello-world.pic.o

6 directories, 7 files

Now test your freshly built binary, which is:

$ bazel-bin/main/hello-world

This results in a printed “Hello world” message.

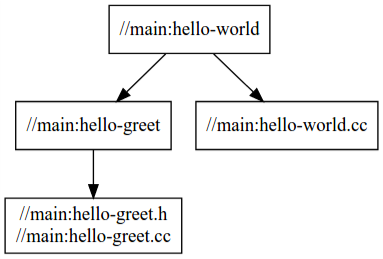

Here’s the dependency graph of Stage 1:

Summary: stage 1

Now that you have completed your first build, you have a basic idea of how a build is structured. In the next stage, you will add complexity by adding another target.

Stage 2: multiple build targets

While a single target is sufficient for small projects, you may want to split larger projects into multiple targets and packages. This allows for fast incremental builds – that is, Bazel only rebuilds what’s changed – and speeds up your builds by building multiple parts of a project at once. This stage of the tutorial adds a target, and the next adds a package.

This is the directory you are working with for Stage 2:

├──stage2

│ ├── main

│ │ ├── BUILD

│ │ ├── hello-world.cc

│ │ ├── hello-greet.cc

│ │ └── hello-greet.h

│ └── WORKSPACE

Take a look below at the BUILD file in the cpp-tutorial/stage2/main directory:

cc_library(

name = "hello-greet",

srcs = ["hello-greet.cc"],

hdrs = ["hello-greet.h"],

)

cc_binary(

name = "hello-world",

srcs = ["hello-world.cc"],

deps = [

":hello-greet",

],

)

With this BUILD file, Bazel first builds the hello-greet library (using Bazel’s built-in cc_library rule), then the hello-world binary. The deps attribute in the hello-world target tells Bazel that the hello-greet library is required to build the hello-world binary.

Before you can build this new version of the project, you need to change directories, switching to the cpp-tutorial/stage2 directory by running:

$ cd ../cpp-tutorial/stage2

Now you can build the new binary using the following familiar command:

$ bazel build //main:hello-world

Once again, Bazel produces something that looks like this:

~/github/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage2$bazel build //main:hello-world

WARNING: Ignoring JAVA_HOME, because it must point to a JDK, not a JRE.

Starting local Bazel server and connecting to it...

INFO: Analyzed target //main:hello-world (34 packages loaded, 152 targets configured).

INFO: Found 1 target...

Target //main:hello-world up-to-date:

bazel-bin/main/hello-world

INFO: Elapsed time: 3.981s, Critical Path: 0.23s

INFO: 7 processes: 4 internal, 3 processwrapper-sandbox.

INFO: Build completed successfully, 7 total actions

Now you can test your freshly built binary, which returns another “Hello world”:

$ bazel-bin/main/hello-world

If you now modify hello-greet.cc and rebuild the project, Bazel only recompiles that file.

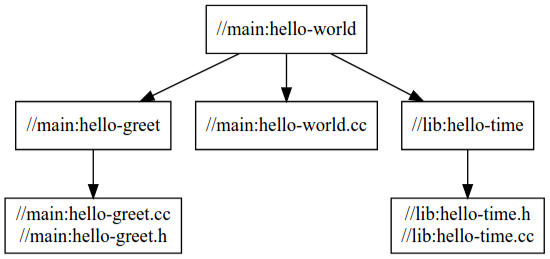

Looking at the dependency graph, you can see that hello-world depends on the same inputs as it did before, but the structure of the build is different:

Summary: stage 2

You’ve now built the project with two targets. The

hello-worldtarget builds one source file and depends on one other target (//main:hello-greet), which builds two additional source files. In the next section, take it a step further and add another package.

Stage 3: multiple packages

This next stage adds another layer of complication and builds a project with multiple packages. Take a look below at the structure and contents of the cpp-tutorial/stage3 directory:

──stage3

├── main

│ ├── BUILD

│ ├── hello-world.cc

│ ├── hello-greet.cc

│ └── hello-greet.h

├── lib

│ ├── BUILD

│ ├── hello-time.cc

│ └── hello-time.h

└── WORKSPACE

You can see that now there are two sub-directories, and each contains a BUILD file. Therefore, to Bazel, the workspace now contains two packages: lib and main.

Take a look at the lib/BUILD file:

cc_library(

name = "hello-time",

srcs = ["hello-time.cc"],

hdrs = ["hello-time.h"],

visibility = ["//main:__pkg__"],

)

And at the main/BUILD file:

cc_library(

name = "hello-greet",

srcs = ["hello-greet.cc"],

hdrs = ["hello-greet.h"],

)

cc_binary(

name = "hello-world",

srcs = ["hello-world.cc"],

deps = [

":hello-greet",

"//lib:hello-time",

],

)

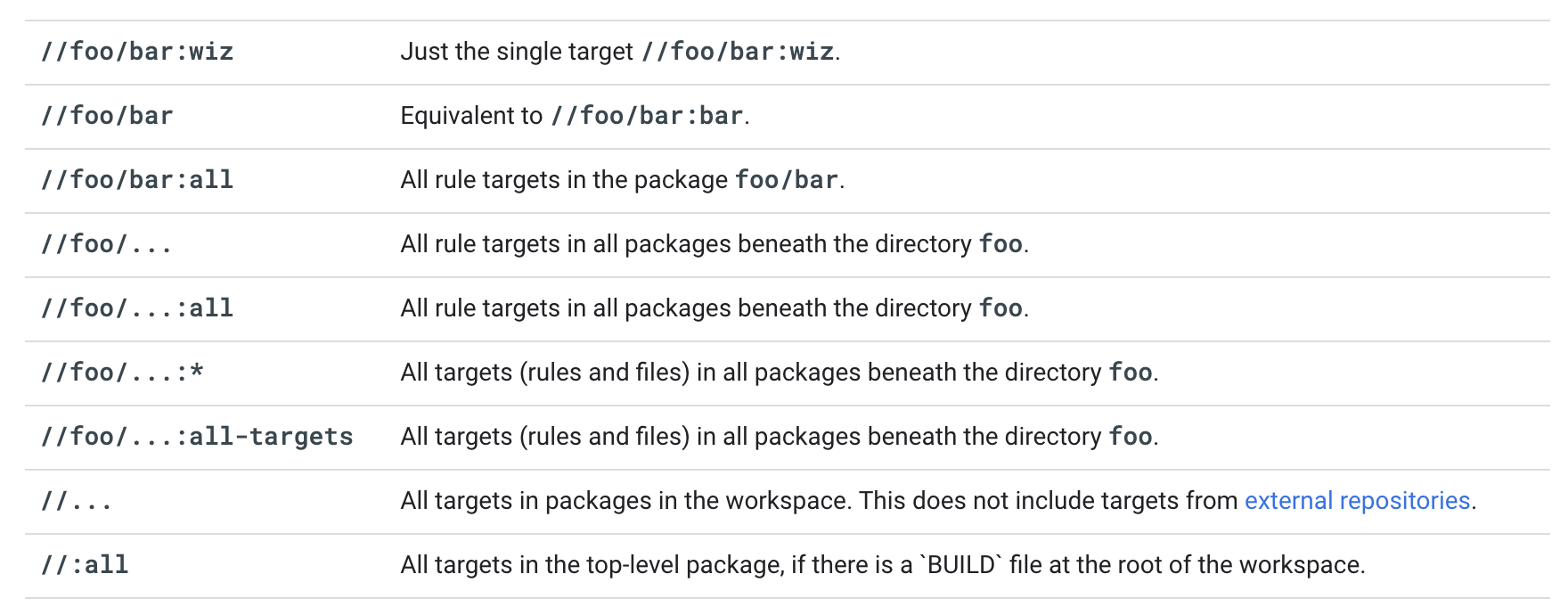

The hello-world target in the main package depends on the hello-time target in the lib package (hence the target label //lib:hello-time) - Bazel knows this through the deps attribute. You can see this reflected in the dependency graph:

For the build to succeed, you make the //lib:hello-time target in lib/BUILD explicitly visible to targets in main/BUILD using the visibility attribute. This is because by default targets are only visible to other targets in the same BUILD file. Bazel uses target visibility to prevent issues such as libraries containing implementation details leaking into public APIs.

Now build this final version of the project. Switch to the cpp-tutorial/stage3 directory by running:

$ cd ../cpp-tutorial/stage3

Once again, run the following command:

$ bazel build //main:hello-world

Bazel produces something that looks like this:

~/github/examples/cpp-tutorial/stage3$bazel build //main:hello-world

WARNING: Ignoring JAVA_HOME, because it must point to a JDK, not a JRE.

INFO: Analyzed target //main:hello-world (35 packages loaded, 155 targets configured).

INFO: Found 1 target...

Target //main:hello-world up-to-date:

bazel-bin/main/hello-world

INFO: Elapsed time: 2.172s, Critical Path: 0.25s

INFO: 8 processes: 4 internal, 4 processwrapper-sandbox.

INFO: Build completed successfully, 8 total actions

Now test the last binary of this tutorial for a final Hello world message:

$ bazel-bin/main/hello-world

Summary: stage 3

You’ve now built the project as two packages with three targets and understand the dependencies between them, which equips you to go forth and build future projects with Bazel. In the next section, take a look at how to continue your Bazel journey.

Next steps

You’ve now completed your first basic build with Bazel, but this is just the start. Here are some more resources to continue learning with Bazel:

- To keep focusing on C++, read about common C++ build use cases.

- To get started with building other applications with Bazel, see the tutorials for Java, Android application, or iOS application.

- To learn more about working with local and remote repositories, read about external dependencies.

- To learn more about Bazel’s other rules, see this reference guide.

Happy building!

Common C++ Build Use Cases

Here you will find some of the most common use cases for building C++ projects with Bazel. If you have not done so already, get started with building C++ projects with Bazel by completing the tutorial Introduction to Bazel: Build a C++ Project.

For information on cc_library and hdrs header files, see cc_library.

Including multiple files in a target

You can include multiple files in a single target with glob. For example:

cc_library(

name = "build-all-the-files",

srcs = glob(["*.cc"]),

hdrs = glob(["*.h"]),

)

With this target, Bazel will build all the .cc and .h files it finds in the same directory as the BUILD file that contains this target (excluding subdirectories).

考虑包含子目录的情况:

cc_library(

name = "build-all-the-files-include-subdirectories",

srcs = glob(["**/*.cc"]),

hdrs = glob(["**/*.h"]),

)

Using transitive includes

If a file includes a header, then any rule with that file as a source (that is, having that file in the srcs, hdrs, or textual_hdrs attribute) should depend on the included header’s library rule. Conversely, only direct dependencies need to be specified as dependencies.

For example, suppose sandwich.h includes bread.h and bread.h includes flour.h. sandwich.h doesn’t include flour.h (who wants flour in their sandwich?), so the BUILD file would look like this:

cc_library(

name = "sandwich",

srcs = ["sandwich.cc"],

hdrs = ["sandwich.h"],

deps = [":bread"],

)

cc_library(

name = "bread",

srcs = ["bread.cc"],

hdrs = ["bread.h"],

deps = [":flour"],

)

cc_library(

name = "flour",

srcs = ["flour.cc"],

hdrs = ["flour.h"],

)

Here, the sandwich library depends on the bread library, which depends on the flour library.

Adding include paths

Sometimes you cannot (or do not want to) root include paths at the workspace root. Existing libraries might already have an include directory that doesn’t match its path in your workspace. For example, suppose you have the following directory structure:

└── my-project

├── legacy

│ └── some_lib

│ ├── BUILD

│ ├── include

│ │ └── some_lib.h

│ └── some_lib.cc

└── WORKSPACE

Bazel will expect some_lib.h to be included as legacy/some_lib/include/some_lib.h, but suppose some_lib.cc includes “some_lib.h”. To make that include path valid, legacy/some_lib/BUILD will need to specify that the some_lib/include directory is an include directory:

cc_library(

name = "some_lib",

srcs = ["some_lib.cc"],

hdrs = ["include/some_lib.h"],

copts = ["-Ilegacy/some_lib/include"],

)

This is especially useful for external dependencies, as their header files must otherwise be included with a / prefix.

Including external libraries

Suppose you are using Google Test. You can use one of the repository functions in the WORKSPACE file to download Google Test and make it available in your repository:

load("@bazel_tools//tools/build_defs/repo:http.bzl", "http_archive")

http_archive(

name = "gtest",

url = "https://github.com/google/googletest/archive/release-1.10.0.zip",

sha256 = "94c634d499558a76fa649edb13721dce6e98fb1e7018dfaeba3cd7a083945e91",

build_file = "@//:gtest.BUILD",

)

Note: If the destination already contains a

BUILDfile, you can leave out thebuild_fileattribute.

Then create gtest.BUILD, a BUILD file used to compile Google Test. Google Test has several “special” requirements that make its cc_library rule more complicated:

googletest-release-1.10.0/src/gtest-all.cc#includesall other files ingoogletest-release-1.10.0/src/:exclude it from the compile to prevent link errors for duplicate symbols.- It uses header files that are relative to the

googletest-release-1.10.0/include/directory (“gtest/gtest.h”), so you must add that directory to the include paths. - It needs to link in

pthread, so add that as alinkopt.

The final rule therefore looks like this:

cc_library(

name = "main",

srcs = glob(

["googletest-release-1.10.0/src/*.cc"],

exclude = ["googletest-release-1.10.0/src/gtest-all.cc"]

),

hdrs = glob([

"googletest-release-1.10.0/include/**/*.h",

"googletest-release-1.10.0/src/*.h"

]),

copts = [

"-Iexternal/gtest/googletest-release-1.10.0/include",

"-Iexternal/gtest/googletest-release-1.10.0"

],

linkopts = ["-pthread"],

visibility = ["//visibility:public"],

)

This is somewhat messy(凌乱的): everything is prefixed with googletest-release-1.10.0 as a byproduct of the archive’s structure. You can make http_archive strip this prefix by adding the strip_prefix attribute:

load("@bazel_tools//tools/build_defs/repo:http.bzl", "http_archive")

http_archive(

name = "gtest",

url = "https://github.com/google/googletest/archive/release-1.10.0.zip",

sha256 = "94c634d499558a76fa649edb13721dce6e98fb1e7018dfaeba3cd7a083945e91",

build_file = "@//:gtest.BUILD",

strip_prefix = "googletest-release-1.10.0",

)

Then gtest.BUILD would look like this:

cc_library(

name = "main",

srcs = glob(

["src/*.cc"],

exclude = ["src/gtest-all.cc"]

),

hdrs = glob([

"include/**/*.h",

"src/*.h"

]),

copts = ["-Iexternal/gtest/include"],

linkopts = ["-pthread"],

visibility = ["//visibility:public"],

)

Now cc_ rules can depend on @gtest//:main.

Writing and running C++ tests

For example, you could create a test ./test/hello-test.cc, such as:

#include "gtest/gtest.h"

#include "main/hello-greet.h"

TEST(HelloTest, GetGreet) {

EXPECT_EQ(get_greet("Bazel"), "Hello Bazel");

}

Then create ./test/BUILD file for your tests:

cc_test(

name = "hello-test",

srcs = ["hello-test.cc"],

copts = ["-Iexternal/gtest/include"],

deps = [

"@gtest//:main",

"//main:hello-greet",

],

)

To make hello-greet visible to hello-test, you must add "//test:__pkg__", to the visibility attribute in ./main/BUILD.

Now you can use bazel test to run the test.

bazel test test:hello-test

This produces the following output:

INFO: Found 1 test target...

Target //test:hello-test up-to-date:

bazel-bin/test/hello-test

INFO: Elapsed time: 4.497s, Critical Path: 2.53s

//test:hello-test PASSED in 0.3s

Executed 1 out of 1 tests: 1 test passes.

More: https://google.github.io/googletest/quickstart-bazel.html

Adding dependencies on precompiled libraries

If you want to use a library of which you only have a compiled version (for example, headers and a .so file) wrap it in a cc_library rule:

cc_library(

name = "mylib",

srcs = ["mylib.so"],

hdrs = ["mylib.h"],

)

This way, other C++ targets in your workspace can depend on this rule.

Build programs with Bazel

Available commands

bazel help

- analyze-profile: Analyzes build profile data.

- aquery: Executes a query on the post-analysis action graph.

- build: Builds the specified targets.

- canonicalize-flags: Canonicalize Bazel flags.

- clean: Removes output files and optionally stops the server.

- cquery: Executes a post-analysis dependency graph query.

- dump: Dumps the internal state of the Bazel server process.

- help: Prints help for commands, or the index.

- info: Displays runtime info about the bazel server.

- fetch: Fetches all external dependencies of a target.

- mobile-install: Installs apps on mobile devices.

- query: Executes a dependency graph query.

- run: Runs the specified target.

- shutdown: Stops the Bazel server.

- test: Builds and runs the specified test targets.

- version: Prints version information for Bazel.

Getting help

bazel help command: Prints help and options for command.- bazel help startup_options: Options for the JVM hosting Bazel.

- bazel help target-syntax: Explains the syntax for specifying targets.

bazel help info-keys: Displays a list of keys used by the info command.

The bazel tool performs many functions, called commands. The most commonly used ones are bazel build and bazel test. You can browse the online help messages using bazel help.

Building one target

bazel build //foo

Building multiple targets

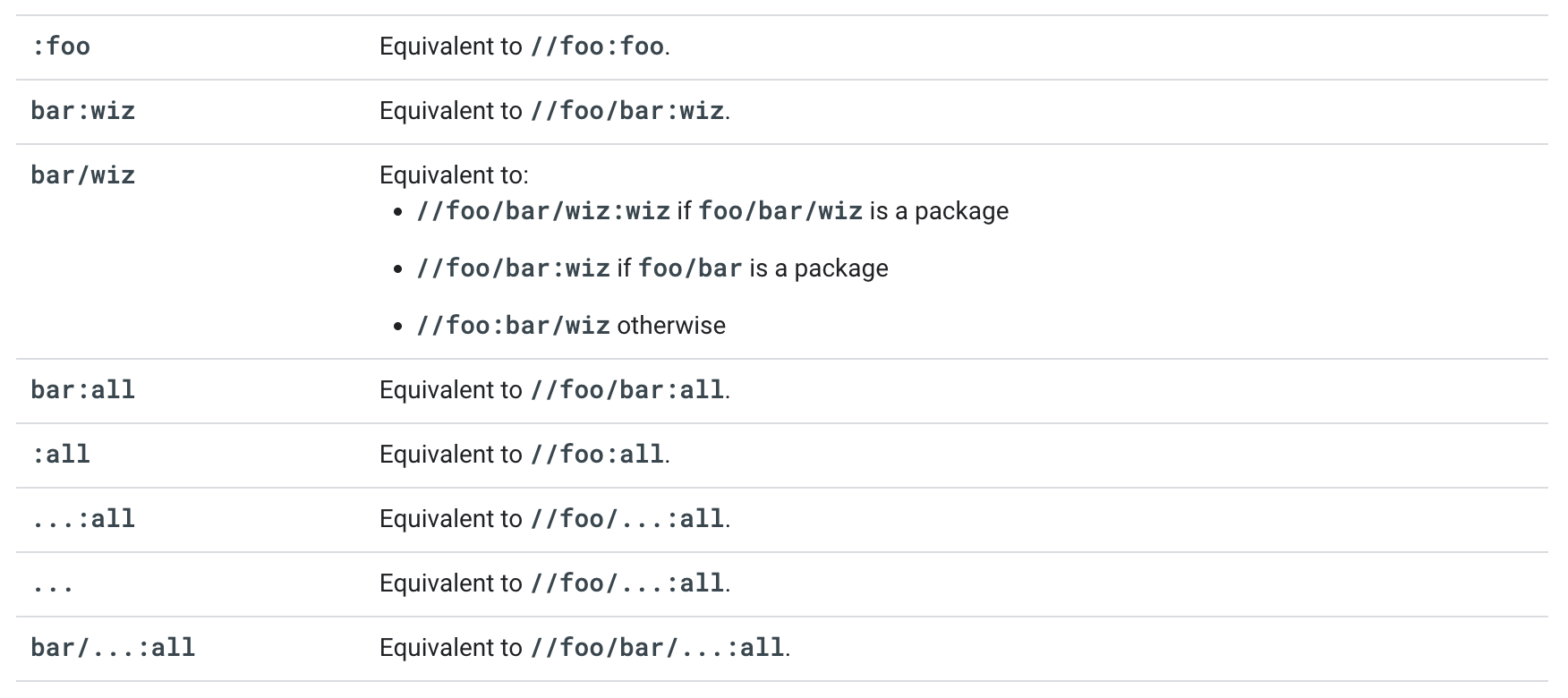

Bazel allows a number of ways to specify the targets to be built. Collectively, these are known as target patterns. This syntax is used in commands like build, test, or query.

All target patterns starting with // are resolved relative to the current workspace.

Target patterns that do not begin with // are resolved relative to the current working directory. These examples assume a working directory of foo:

Fetching external dependencies

By default, Bazel will download and symlink external dependencies during the build. However, this can be undesirable, either because you’d like to know when new external dependencies are added or because you’d like to “prefetch” dependencies (say, before a flight where you’ll be offline). If you would like to prevent new dependencies from being added during builds, you can specify the --fetch=false flag. Note that this flag only applies to repository rules that do not point to a directory in the local file system. Changes, for example, to local_repository, new_local_repository and Android SDK and NDK repository rules will always take effect regardless of the value --fetch .

If you disallow fetching during builds and Bazel finds new external dependencies, your build will fail.

You can manually fetch dependencies by running bazel fetch. If you disallow during-build fetching, you’ll need to run bazel fetch:

- Before you build for the first time.

- After you add a new external dependency.

Once it has been run, you should not need to run it again until the WORKSPACE file changes.

fetch takes a list of targets to fetch dependencies for. For example, this would fetch dependencies needed to build //foo:bar and //bar:baz:

bazel fetch //foo:bar //bar:baz

To fetch all external dependencies for a workspace, run:

bazel fetch //...

Commands and Options

This page covers the options that are available with various Bazel commands, such as bazel build, bazel run, and bazel test. This page is a companion to the list of Bazel’s commands in Build with Bazel.

Options

The following sections describe the options available during a build. When --long is used on a help command, the on-line help messages provide summary information about the meaning, type and default value for each option.

Most options can only be specified once. When specified multiple times, the last instance wins. Options that can be specified multiple times are identified in the on-line help with the text ‘may be used multiple times’.

$bazel help build --short

[bazel release 6.2.1]

Usage: bazel build <options> <targets>

Builds the specified targets, using the options.

See 'bazel help target-syntax' for details and examples on how to

specify targets to build.

Options that appear before the command and are parsed by the client:

--distdir

--[no]experimental_repository_cache_hardlinks

--[no]experimental_repository_cache_urls_as_default_canonical_id

--[no]experimental_repository_disable_download

--experimental_repository_downloader_retries

--experimental_scale_timeouts

--http_timeout_scaling

--repository_cache

$bazel help build --long | head -n50

[bazel release 6.2.1]

Usage: bazel build <options> <targets>

Builds the specified targets, using the options.

See 'bazel help target-syntax' for details and examples on how to

specify targets to build.

Options that appear before the command and are parsed by the client:

--distdir (a path; may be used multiple times)

Additional places to search for archives before accessing the network to

download them.

Tags: bazel_internal_configuration

--[no]experimental_repository_cache_hardlinks (a boolean; default: "false")

If set, the repository cache will hardlink the file in case of a cache hit,

rather than copying. This is intended to save disk space.

Tags: bazel_internal_configuration

Package location

--package_path

This option specifies the set of directories that are searched to find the BUILD file for a given package.

Error checking

These options control Bazel’s error-checking and/or warnings.

--[no]check_visibility--output_filter=regex

Tool flags

These options control which options Bazel will pass to other tools.

--copt=cc-option

This option takes an argument which is to be passed to the compiler. The argument will be passed to the compiler whenever it is invoked for preprocessing, compiling, and/or assembling C, C++, or assembler code. It will not be passed when linking.

This option can be used multiple times. For example:

% bazel build --copt="-g0" --copt="-fpic" //foo

will compile the foo library without debug tables, generating position-independent code.

Note: Changing –copt settings will force a recompilation of all affected object files. Also note that copts values listed in specific cc_library or cc_binary build rules will be placed on the compiler command line after these options.

Warning: C++-specific options (such as -fno-implicit-templates) should be specified in –cxxopt, not in –copt. Likewise, C-specific options (such as -Wstrict-prototypes) should be specified in –conlyopt, not in copt. Similarly, compiler options that only have an effect at link time (such as -l) should be specified in –linkopt, not in –copt.

--cxxopt=cc-option

This option takes an argument which is to be passed to the compiler when compiling C++ source files.

This is similar to --copt, but only applies to C++ compilation, not to C compilation or linking. So you can pass C++-specific options (such as -fpermissive or -fno-implicit-templates) using --cxxopt.

For example:

% bazel build --cxxopt="-fpermissive" --cxxopt="-Wno-error" //foo/cruddy_code

Note: copts parameters listed in specific cc_library or cc_binary build rules are placed on the compiler command line after these options.

--linkopt=linker-option

This option takes an argument which is to be passed to the compiler when linking.

This is similar to --copt, but only applies to linking, not to compilation. So you can pass compiler options that only make sense at link time (such as -lssp or -Wl,--wrap,abort) using --linkopt. For example:

% bazel build --copt="-fmudflap" --linkopt="-lmudflap" //foo/buggy_code

Build rules can also specify link options in their attributes. This option’s settings always take precedence. Also see cc_library.linkopts.

--strip (always|never|sometimes)

This option determines whether Bazel will strip debugging information from all binaries and shared libraries, by invoking the linker with the -Wl,--strip-debug option. --strip=always means always strip debugging information. --strip=never means never strip debugging information. The default value of --strip=sometimes means strip if the --compilation_mode is fastbuild.

% bazel build --strip=always //foo:bar

will compile the target while stripping debugging information from all generated binaries.

Note: If you want debugging information, it’s not enough to disable stripping; you also need to make sure that the debugging information was generated by the compiler, which you can do by using either -c dbg or –copt -g.

Build semantics

These options affect the build commands and/or the output file contents.

--compilation_mode (fastbuild|opt|dbg) (-c)

The --compilation_mode option (often shortened to -c, especially -c opt) takes an argument of fastbuild, dbg or opt, and affects various C/C++ code-generation options, such as the level of optimization and the completeness of debug tables. Bazel uses a different output directory for each different compilation mode, so you can switch between modes without needing to do a full rebuild every time.

fastbuild means build as fast as possible: generate minimal debugging information (-gmlt -Wl,-S), and don’t optimize. This is the default. Note: -DNDEBUG will not be set.

dbg means build with debugging enabled (-g), so that you can use gdb (or another debugger).

opt means build with optimization enabled and with assert() calls disabled (-O2 -DNDEBUG). Debugging information will not be generated in opt mode unless you also pass --copt -g.

--action_env=VAR=VALUE

Specifies the set of environment variables available during the execution of all actions. Variables can be either specified by name, in which case the value will be taken from the invocation environment, or by the name=value pair which sets the value independent of the invocation environment.

This --action_env flag can be specified multiple times. If a value is assigned to the same variable across multiple --action_env flags, the latest assignment wins.

Execution strategy

These options affect how Bazel will execute the build. They should not have any significant effect on the output files generated by the build. Typically their main effect is on the speed of the build.

--spawn_strategy=strategy

This option controls where and how commands are executed.

standalone causes commands to be executed as local subprocesses. This value is deprecated. Please use local instead.

sandboxed causes commands to be executed inside a sandbox on the local machine. This requires that all input files, data dependencies and tools are listed as direct dependencies in the srcs, data and tools attributes. Bazel enables local sandboxing by default, on systems that support sandboxed execution.

local causes commands to be executed as local subprocesses.

worker causes commands to be executed using a persistent worker, if available.

docker causes commands to be executed inside a docker sandbox on the local machine. This requires that docker is installed.

remote causes commands to be executed remotely; this is only available if a remote executor has been configured separately.

More: What are Bazel’s strategies?

--jobs=n (-j)

This option, which takes an integer argument, specifies a limit on the number of jobs that should be executed concurrently during the execution phase of the build.

Note: The number of concurrent jobs that Bazel will run is determined not only by the –jobs setting, but also by Bazel’s scheduler, which tries to avoid running concurrent jobs that will use up more resources (RAM or CPU) than are available, based on some (very crude) estimates of the resource consumption of each job. The behavior of the scheduler can be controlled by the –local_ram_resources option.

--local_{ram,cpu}_resources resources or resource expression

These options specify the amount of local resources (RAM in MB and number of CPU logical cores) that Bazel can take into consideration when scheduling build and test activities to run locally. They take an integer, or a keyword (HOST_RAM or HOST_CPUS) optionally followed by [-|*float] (for example, --local_cpu_resources=2, --local_ram_resources=HOST_RAM*.5, --local_cpu_resources=HOST_CPUS-1). The flags are independent; one or both may be set. By default, Bazel estimates the amount of RAM and number of CPU cores directly from the local system’s configuration.

Verbosity

These options control the verbosity of Bazel’s output, either to the terminal, or to additional log files.

--explain=logfile

This option, which requires a filename argument, causes the dependency checker in bazel build’s execution phase to explain, for each build step, either why it is being executed, or that it is up-to-date. The explanation is written to logfile.

If you are encountering unexpected rebuilds, this option can help to understand the reason. Add it to your .bazelrc so that logging occurs for all subsequent builds, and then inspect the log when you see an execution step executed unexpectedly. This option may carry a small performance penalty, so you might want to remove it when it is no longer needed.

--verbose_explanations

This option increases the verbosity of the explanations generated when the --explain option is enabled.

In particular, if verbose explanations are enabled, and an output file is rebuilt because the command used to build it has changed, then the output in the explanation file will include the full details of the new command (at least for most commands).

Using this option may significantly increase the length of the generated explanation file and the performance penalty of using --explain.

If --explain is not enabled, then --verbose_explanations has no effect.

--profile=file

This option, which takes a filename argument, causes Bazel to write profiling data into a file. The data then can be analyzed or parsed using the bazel analyze-profile command. The Build profile can be useful in understanding where Bazel’s build command is spending its time.

--show_result=n

This option controls the printing of result information at the end of a bazel build command. By default, if a single build target was specified, Bazel prints a message stating whether or not the target was successfully brought up-to-date, and if so, the list of output files that the target created. If multiple targets were specified, result information is not displayed.

While the result information may be useful for builds of a single target or a few targets, for large builds (such as an entire top-level project tree), this information can be overwhelming and distracting; this option allows it to be controlled. --show_result takes an integer argument, which is the maximum number of targets for which full result information should be printed. By default, the value is 1. Above this threshold, no result information is shown for individual targets. Thus zero causes the result information to be suppressed always, and a very large value causes the result to be printed always.

--subcommands (-s)

This option causes Bazel’s execution phase to print the full command line for each command prior to executing it.

--subcommands=pretty_print may be passed to print the arguments of the command as a list rather than as a single line. This may help make long command lines more readable.

--verbose_failures

This option causes Bazel’s execution phase to print the full command line for commands that failed. This can be invaluable(非常有用的) for debugging a failing build.

Failing commands are printed in a Bourne shell compatible syntax, suitable for copying and pasting to a shell prompt.

Workspace status

Use these options to “stamp” Bazel-built binaries: to embed additional information into the binaries, such as the source control revision or other workspace-related information. You can use this mechanism with rules that support the stamp attribute, such as genrule, cc_binary, and more.

--workspace_status_command=program

This flag lets you specify a binary that Bazel runs before each build. The program can report information about the status of the workspace, such as the current source control revision.

The flag’s value must be a path to a native program. On Linux/macOS this may be any executable.

The program should print zero or more key/value pairs to standard output, one entry on each line, then exit with zero (otherwise the build fails). The key names can be anything but they may only use upper case letters and underscores. The first space after the key name separates it from the value. The value is the rest of the line (including additional whitespaces). Neither the key nor the value may span multiple lines. Keys must not be duplicated.

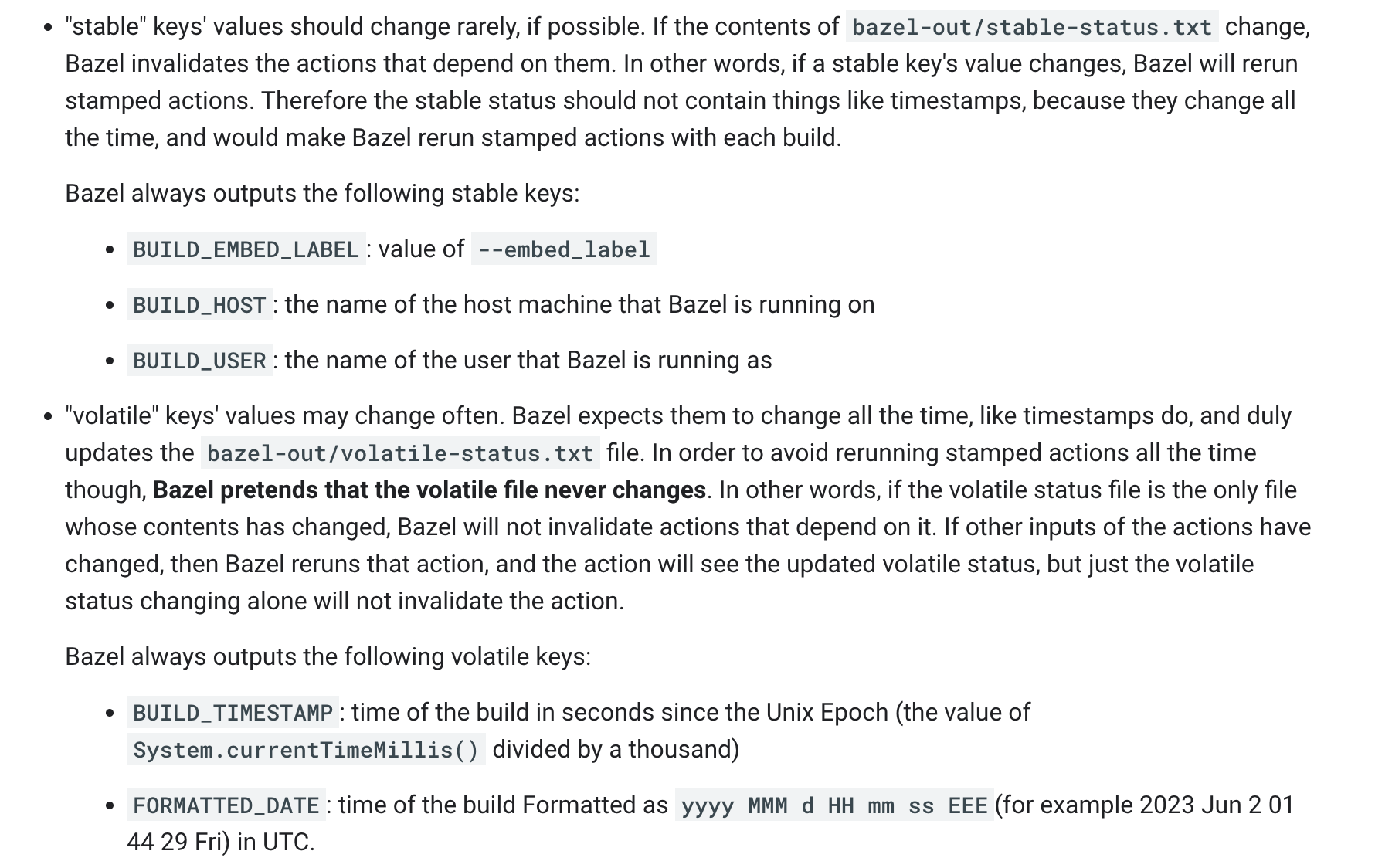

Bazel partitions the keys into two buckets: “stable” and “volatile”. (The names “stable” and “volatile” are a bit counter-intuitive, so don’t think much about them.)

Bazel then writes the key-value pairs into two files:

bazel-out/stable-status.txtcontains all keys and values where the key’s name starts withSTABLE_bazel-out/volatile-status.txtcontains the rest of the keys and their values

The contract is: