Protocol Buffers in Action

- 最佳实践

- proto2 和 proto3的版本差异

- 选择正确的数据类型

- Protocol Buffers Well-Known Types

- 服务设计

- 协议更新

- Defining A Message Type (Step by Step)

- Specifying Field Types

- Assigning Field Numbers

- Specifying Field Rules

- Adding More Message Types

- Adding Comments

- Reserved Fields

- What’s Generated From Your

.proto? - Default Values

- Using Other Message Types

- Importing Definitions

- Nested Types

- Updating A Message Type

- Unknown Fields

- Any

- Oneof

- Maps

- Packages

- Defining Services

- JSON

- Options

- Generating Your Classes

- Encoding

- Other

- Protocol Buffer Basics: C++

- C++ API

- 关键结构

- 性能测试

- 对比 FlatBuffers

- Arena Allocation

- PB Code Style

- Q&A

- Tools

- ChangeLog

- Refer

最佳实践

参考官方 Style Guide

Note that protocol buffer style has evolved over time, so it is likely that you will see

.protofiles written in different conventions or styles. Please respect the existing style when you modify these files. Consistency is key. However, it is best to adopt the current best style when you are creating a new.protofile.

工具

- Protobuf 编译器。尽量采用高版本的编译器,高版本的编译器向下兼容,即使是

3.x版的编译器也依然兼容proto2。 - 由于不同版本的

protoc生成的代码不兼容,因此在代码库中应该只放.proto文件,不应当放protoc编译生成的代码,这些文件应当由构建系统来处理。

组织结构

- 目录结构。目录结构建议和

package名保持一致。比如a.b表示在a/b目录中。 - 文件名。

.proto源文件名统一用小蛇形(例如:lower_snake_case.proto)命名。 - 避免庞大的 proto 定义。避免在一个 proto 文件中定义过多的内容。不但造成不必要的耦合,还会降低编译速度。一个 proto 文件里只放密切相关的一组定义,依赖的定义应当放在其他 proto 文件中,通过

import的方式导入。

文件格式(File structure)

All files should be ordered in the following manner:

- License header (if applicable)

- File overview

- Syntax

- Package

- Imports (sorted)

- File options

- Everything else

- 文件编码。统一采用

UTF-8编码。 - 缩进。采用

2空格缩进,和Google官方规范保持一致。 - 注释。不仅可以在阅读代码时提供帮助信息,还能在程序中通过反射机制获取注释信息。

.proto文件整体结构。按照版权信息,文件头注释,syntax语句,package语句,import语句,文件option,其他内容的顺序组织定义,每个部分和其他部分之间空一行。- 2014年Google在2.6.1发布后,版本号突然升到3.0,并引入了一种新的

proto3语法,简化了语法,但是和原来的proto2并不完全兼容。新版本的编译器对于不带syntax语句的.proto文件,默认为proto2,但是会输出警告。.proto文件都带上syntax语句显式指定版本不但可以消除这个警告,同时也更清晰。 .proto文件必须有package声明。package名统一小写,用点分割。可以按业务、模块需要引入子package。import用于导入其他.proto文件,按照字母顺序排列,不同来源的import之间可以用空行分组,不要导入未用到的文件。- Protobuf支持设置一些文件级别的选项,用于控制代码生成等目的。例如:

option optimize_for = CODE_SIZE

- 2014年Google在2.6.1发布后,版本号突然升到3.0,并引入了一种新的

- 命名

- 消息名,为名词短语,采用大驼峰(例如:

CamelCase)命名法。 - 枚举类型名,同消息名,采用大驼峰(例如:

CamelCase)命名法。 - 枚举值名,采用大蛇形(例如:

SNAKE_CASE)命名法。不要受C++影响以k开头。因为protobuf是跨语言的,在Java、Python等大部分语言,包括C++里传统上都允许用全大写表示常量。- 字段名,采用小蛇形(例如:

snake_case)命名法。protoc生成不同类型的目标语言的代码时,会把字段名自动转换为符合其代码规范的命名格式repeated字段名用单词的复数- 每个消息的字段从

1开始,依次递增。如果需要预留某些字段,请使用reserved语句进行标记并添加注释进行解释;如果需要废弃现存字段,请使用deprecated选项进行标记并添加注释进行解释。对于废弃的字段,建议不要删除,这样可以更好的说明编号不连续的原因,提高可维护性 - 不要使用

required字段。对于proto2,required字段会对未来的兼容带来潜在的风险。proto3中已经取消了required字段。详情参见文档 default值等同于类型的默认值时,不需要写出

- 服务名,采用大驼峰(例如:

CamelCase)命名,以Service结尾,例如:QueryService - 方法名,采用大驼峰(例如:

CamelCase)命名,应当是动词或者动词短语,例如:Query

- 字段名,采用小蛇形(例如:

- 消息名,为名词短语,采用大驼峰(例如:

下面是一个简单的.proto模版。

// Copyright (C) 2021 $company Inc. All rights reserved.

//

// This is a sample protobuf source code.

syntax = "proto3";

package $company.protobuf.style.example;

import "google/protobuf/nested_extension.proto";

import "google/protobuf/nested_extension_lite.proto";

option optimize_for = LITE_RUNTIME;

message MyNestedExtension {

optional bool is_extension = 1;

}

message MyNestedExtensionLite {

extend MessageLiteToBeExtended {

optional MessageLiteToBeExtended recursiveExtensionLite = 3;

}

}

message Person {

reserved 5, 7, 9 to 11; // 因为 xxx 原因预留

reserved "blood_type"; // 下一版本使用

optional string name = 1;

optional int32 age = 2;

optional bool married = 3 [deprecated=true]; // 隐私条例更新, 不再记录婚姻状态

optional int32 gender = 4;

}

proto2 和 proto3的版本差异

- proto3 去掉了

required字段,所有的singular字段都是optional的,因此也去掉了这两个关键字 - proto3 去掉了字段的默认值

- proto3 去掉了扩展,但是创建选项依然需要用 proto2 的扩展语法

- Proto3 的早期版本去掉了自动保留未知字段功能,直到3.5 版才恢复

版本兼容性:可以导入 proto3 消息类型并在 proto2 消息中使用它们,反之亦然。 但是,不能在 proto3 语法中使用 proto2 枚举。

选择正确的数据类型

Protobuf支持多种数据类型,这些数据类型都有不同的设计用意,用得好可以获得较好的性能,节省存储空间,保证良好的兼容性,反之则可能会带来麻烦。因此需要掌握规律,慎重选择。

整数类型

- 对于大部分场景,优先选用

int32,如果不够考虑用int64。 int64编译生成的消息会多占存储空间,但是序列化后并不比int32多费空间,因此,如果数值将来可能很大,且在目标语言环境下也没有性能和空间差异的问题,可以大胆采用。需要注意的是,在接口需要提供Json类型返回值时,int64在序列化时会自动转为string。int32和int64对绝对值小的负数编码很低效,sint32和sint64适合于经常会出现这种负数的情况,必要时可以谨慎选择。但是需要注意他们和int32及int64的编码方式并不兼容。fixed32、fixed64、sfixed32、sfixed64适合于数字通常很大(阈值分别是28位和56位)的场合,比如 IP 地址、hash 值等,编码更高效。但是 fixed 类型和常规的int32、int64不兼容,也不兼容其他整数类型。

浮点数类型

float和double都是按定长方式保存的,因此互不兼容。- 虽然用

float会节省一些空间,但要考虑未来的精度和值域的兼容性,因此建议通常还是优先用double。 - 大量的浮点数,比如需要大量创建的消息对象,个数很多的

repeated的字段等,用float保存时可以节省一些空间,在精度和未来的扩展都不是问题的情况下,可以考虑采用。

string 和 bytes 类型

- 用

string类型来表示UTF-8(包括ASCII)能表示的文本信息,比如文字消息,URL,ASCII化编码后的二进制数据(base64编码,十六进制文本表示的MD5等)。 - 用

bytes类型来表示二进制字节流(通常不可读),比如序列化后的内容,二进制表示的MD5,非UTF8编码能表示的文本(比如GBK)。 - 如果用

string类型保存非UTF-8兼容的内容,在C++生成的代码中,也会导致运行期警告。

Protocol Buffers Well-Known Types

Empty

A generic empty message that you can re-use to avoid defining duplicated empty messages in your APIs. A typical example is to use it as the request or the response type of an API method. For instance:

service Foo {

rpc Bar(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

}

The JSON representation for Empty is empty JSON object {}.

google.protobuf.Empty 是 Protobuf 中预定义的一个特殊消息类型,用于表示一个空的请求或响应。它在 gRPC 等基于 Protobuf 的通信场景中非常常见,主要目的是简化接口设计,避免为无参数或无返回值的场景定义冗余的消息类型。

用途:

- 表示空输入或空输出。当某个 RPC 方法不需要传递任何参数(或不需要返回任何数据)时,可以用 Empty 作为占位符,替代自定义的空消息类型。

- 标准化接口。使用 Protobuf 官方提供的 Empty 类型,可以保持不同服务之间接口的一致性,避免每个团队重复定义自己的空消息(如 Void、Null 等)。

使用场景:

- 无参数的 RPC 方法

例如,一个简单的健康检查接口,客户端不需要传递任何参数,服务端也只需确认请求是否成功:

service HealthService {

rpc CheckHealth(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

}

- 无需返回值的 RPC 方法

例如,一个删除资源的接口,客户端发送删除请求后,服务端无需返回具体数据,只需确认操作成功:

service ResourceService {

rpc DeleteResource(DeleteRequest) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

}

- 事件通知或心跳机制

在发布-订阅模式中,某些事件可能只需要触发动作,不需要携带数据:

service NotificationService {

rpc OnEventTriggered(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (stream Event);

}

代码示例:

Protobuf 定义:

syntax = "proto3";

import "google/protobuf/empty.proto";

service ExampleService {

rpc DoSomething(google.protobuf.Empty) returns (google.protobuf.Empty);

}

package main

import (

"context"

"google.golang.org/protobuf/types/known/emptypb"

)

type ExampleServiceServer struct{}

func (s *ExampleServiceServer) DoSomething(ctx context.Context, empty *emptypb.Empty) (*emptypb.Empty, error) {

// 执行某些操作,无需输入和输出

return &emptypb.Empty{}, nil

}

注意事项:

- 避免滥用。如果未来接口可能扩展需要参数或返回值,建议提前定义一个自定义的空消息(如 EmptyResponse),以便后续添加字段。而 google.protobuf.Empty 是固定不可扩展的。

- 语言差异。不同编程语言中导入 Empty 的方式可能不同。例如:

- Go: import “google.golang.org/protobuf/types/known/emptypb”

- Java: import com.google.protobuf.Empty;

- 与 void 的区别。在 gRPC 中,不能直接使用 void 作为参数或返回类型,必须通过消息类型占位,这就是 Empty 的作用。

服务设计

- 服务最好放在单独的

.proto文件中。 - 避免在服务定义文件中定义除了请求和回应消息之外的消息类型,非RPC类型定义在其他的

.proto文件中,通过import的方式导入。 - 避免单个服务的方法个数太多。

- 对于已经上线的服务,不得更改服务名、方法名、请求和返回值的类型。

协议更新

对于尚未发布上线的消息定义,可以自由更改。但是任何.proto文件发布后,再修改都会涉及到兼容性问题,因此除非特别必要,尽量不要破坏对先前版本的兼容性。

以下是官方的协议更新说明:

- 请勿更改任何现有字段的字段编号。

int32,uint32,int64,uint64和bool都是兼容的。这意味着可以将字段从这些类型中的一种更改为另一种,而不会破坏向前或向后的兼容性。但是要注意的是,如果解析数值时用的类型和实际编码时用的类型不一致,则等效于在 C++ 中执行强制类型转换,如果数值存在溢出就会导致丢失(例如,如果将 64 位数值按 int32 来读取,它将被截断为 32 位,如果高 32 位非 0 则会丢失)。sint32和sint64彼此兼容,但与其他整数类型不兼容。string和bytes兼容,只要 bytes 的内容是有效的UTF-8。- 如果

bytes包含消息的编码后的内容,则嵌入式消息与bytes兼容。 fixed32与sfixed32兼容,而fixed64与sfixed64兼容,信息不会丢失,但是可能会获得不一样的值的解释方式(比如以sfixed32表示的-1如果用fixed32来读取会得到0xFFFFFFFF)。- 就传输格式而言,

枚举与int32,uint32,int64和uint64兼容(请注意,如果值不合适,将会被截断),但是请注意,在反序列化消息时,客户端代码可能会以不同的方式对待它们。 - 对于

string,bytes和message字段,optional与repeated兼容。当读取方以optional的定义方式解析以repeated的方式序列化的数据时,则如果是原始类型的字段,则将采用最后一个输入值;如果是消息类型的字段,则将合并所有的输入元素。请注意,这对于数值类型(包括布尔值和枚举)通常不安全,repeated的数值类型的字段可以以packed的格式序列化(proto3中默认开启),当读取方的定义是optional字段时,该格式将无法正确解析。 - 将单个可选值更改为新的

oneof的成员是安全且二进制兼容的。如果您确定没有代码一次设置多个可选字段,则将它们移动到一个新建的oneof字段中可能是安全的。将任何字段移动到现有的oneof字段中都是不安全的。 - 只要在更新后的消息类型中不再使用字段号,就可以删除字段。可以重命名该字段,或者添加前缀

OBSOLETE_,或者保留该字段编号,以使.proto的将来的修改不会意外重用该编号。

Defining A Message Type (Step by Step)

syntax = "proto3";

/* SearchRequest represents a search query, with pagination options to

* indicate which results to include in the response. */

message SearchRequest {

string query = 1;

int32 page_number = 2; // Which page number do we want

int32 result_per_page = 3; // Number of results to return per page

enum Corpus {

UNIVERSAL = 0;

WEB = 1;

IMAGES = 2;

LOCAL = 3;

NEWS = 4;

PRODUCTS = 5;

VIDEO = 6;

}

Corpus corpus = 4;

}

message SearchResponse {

...

}

Specifying Field Types

| .proto Type | C++ Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| double | double | |

| float | float | |

| int32 | int32 | Uses variable-length encoding. Inefficient for encoding negative numbers – if your field is likely to have negative values, use sint32 instead. |

| int64 | int64 | Uses variable-length encoding. Inefficient for encoding negative numbers – if your field is likely to have negative values, use sint64 instead. |

| uint32 | uint32 | Uses variable-length encoding. |

| uint64 | uint64 | Uses variable-length encoding. |

| sint32 | int32 | Uses variable-length encoding. Signed int value. These more efficiently encode negative numbers than regular int32s. |

| sint64 | int64 | Uses variable-length encoding. Signed int value. These more efficiently encode negative numbers than regular int64s. |

| fixed32 | uint32 | Always four bytes. More efficient than uint32 if values are often greater than 2^28. |

| fixed64 | uint64 | Always eight bytes. More efficient than uint64 if values are often greater than 2^56. |

| sfixed32 | int32 | Always four bytes. |

| sfixed64 | int64 | Always eight bytes. |

| bool | bool | |

| string | string | A string must always contain UTF-8 encoded or 7-bit ASCII text, and cannot be longer than 2^32. |

| bytes | string | May contain any arbitrary sequence of bytes no longer than 2^32. |

Assigning Field Numbers

- Note that field numbers in the range

1through15take one byte to encode, including the field number and the field’s type. So reserve the numbers1through15for very frequently occurring message elements. Remember to leave some room for frequently occurring elements that might be added in the future. - The smallest field number you can specify is

1, and the largest is2^29 - 1, or536,870,911. You also cannot use the numbers19000through19999, as they are reserved for the Protocol Buffers implementation - the protocol buffer compiler will complain if you use one of these reserved numbers in your.proto. Similarly, you cannot use any previously reserved field numbers.

Specifying Field Rules

Message fields can be one of the following:

singular: a well-formed message can have zero or one of this field (but not more than one). And this is the default field rule for proto3 syntax.repeated: this field can be repeated any number of times (including zero) in a well-formed message. The order of the repeated values will be preserved.

In proto3, repeated fields of scalar numeric types use packed encoding by default.

Adding More Message Types

Multiple message types can be defined in a single .proto file. This is useful if you are defining multiple related messages – so, for example, if you wanted to define the reply message format that corresponds to your SearchResponse message type, you could add it to the same .proto.

Adding Comments

To add comments to your .proto files, use C/C++-style // and /* ... */ syntax.

Reserved Fields

If you update a message type by entirely removing a field, or commenting it out, future users can reuse the field number when making their own updates to the type. This can cause severe issues if they later load old versions of the same .proto, including data corruption, privacy bugs, and so on. One way to make sure this doesn’t happen is to specify that the field numbers (and/or names, which can also cause issues for JSON serialization) of your deleted fields are reserved. The protocol buffer compiler will complain if any future users try to use these field identifiers.

message Foo {

reserved 2, 15, 9 to 11;

reserved "foo", "bar";

}

Note that you can’t mix field names and field numbers in the same reserved statement.

What’s Generated From Your .proto?

When you run the protocol buffer compiler on a .proto, the compiler generates the code in your chosen language you’ll need to work with the message types you’ve described in the file, including getting and setting field values, serializing your messages to an output stream, and parsing your messages from an input stream.

- For

C++, the compiler generates a.hand.ccfile from each.proto, with aclassfor each message type described in your file. - For

Java, the compiler generates a.javafile with a class for each message type, as well as a special Builder classes for creating message class instances. - For

Go, the compiler generates a.pb.gofile with a type for each message type in your file. - …

Default Values

When a message is parsed, if the encoded message does not contain a particular singular element, the corresponding field in the parsed object is set to the default value for that field. These defaults are type-specific.

The default value for repeated fields is empty (generally an empty list in the appropriate language).

Using Other Message Types

You can use other message types as field types. For example, let’s say you wanted to include Result messages in each SearchResponse message – to do this, you can define a Result message type in the same .proto and then specify a field of type Result in SearchResponse:

message SearchResponse {

repeated Result results = 1;

}

message Result {

string url = 1;

string title = 2;

repeated string snippets = 3;

}

Importing Definitions

In the above example, the Result message type is defined in the same file as SearchResponse – what if the message type you want to use as a field type is already defined in another .proto file?

You can use definitions from other .proto files by importing them. To import another .proto’s definitions, you add an import statement to the top of your file:

import "myproject/other_protos.proto";

Nested Types

You can define and use message types inside other message types, as in the following example – here the Result message is defined inside the SearchResponse message:

message SearchResponse {

message Result {

string url = 1;

string title = 2;

repeated string snippets = 3;

}

repeated Result results = 1;

}

If you want to reuse this message type outside its parent message type, you refer to it as _Parent_._Type_:

message SomeOtherMessage {

SearchResponse.Result result = 1;

}

You can nest messages as deeply as you like:

message Outer { // Level 0

message MiddleAA { // Level 1

message Inner { // Level 2

int64 ival = 1;

bool booly = 2;

}

}

message MiddleBB { // Level 1

message Inner { // Level 2

int32 ival = 1;

bool booly = 2;

}

}

}

Updating A Message Type

It’s very simple to update message types without breaking any of your existing code. Just remember the following rules:

- Don’t change the field numbers for any existing fields.

- If you add new fields, any messages serialized by code using your “old” message format can still be parsed by your new generated code. You should keep in mind the default values for these elements so that new code can properly interact with messages generated by old code. Similarly, messages created by your new code can be parsed by your old code: old binaries simply ignore the new field when parsing. See the Unknown Fields section for details.

- Fields can be removed, as long as the field number is not used again in your updated message type. You may want to rename the field instead, perhaps adding the prefix

"OBSOLETE_", or make the field numberreserved, so that future users of your.protocan’t accidentally reuse the number. int32,uint32,int64,uint64, andboolare all compatible – this means you can change a field from one of these types to another without breaking forwards- or backwards-compatibility. If a number is parsed from the wire which doesn’t fit in the corresponding type, you will get the same effect as if you had cast the number to that type in C++ (e.g. if a 64-bit number is read as an int32, it will be truncated to 32 bits).sint32andsint64are compatible with each other but are not compatible with the other integer types.stringandbytesare compatible as long as the bytes are valid UTF-8.- Embedded messages are compatible with

bytesif the bytes contain an encoded version of the message. fixed32is compatible withsfixed32, andfixed64withsfixed64.- For

string,bytes, andmessage fields,optionalis compatible withrepeated. enumis compatible withint32,uint32,int64, anduint64in terms of wire format (note that values will be truncated if they don’t fit).- Changing a single value into a member of a new

oneofis safe and binary compatible. Moving multiple fields into a newoneofmay be safe if you are sure that no code sets more than one at a time. Moving any fields into an existingoneofis not safe.

Unknown Fields

Unknown fields are well-formed protocol buffer serialized data representing fields that the parser does not recognize. For example, when an old binary parses data sent by a new binary with new fields, those new fields become unknown fields in the old binary.

Originally, proto3 messages always discarded unknown fields during parsing, but in version 3.5 we reintroduced the preservation of unknown fields to match the proto2 behavior. In versions 3.5 and later, unknown fields are retained during parsing and included in the serialized output.

Any

The Any message type lets you use messages as embedded types without having their .proto definition. An Any contains an arbitrary serialized message as bytes, along with a URL that acts as a globally unique identifier for and resolves to that message’s type. To use the Any type, you need to import google/protobuf/any.proto.

import "google/protobuf/any.proto";

message ErrorStatus {

string message = 1;

repeated google.protobuf.Any details = 2;

}

Oneof

If you have a message with many fields and where at most one field will be set at the same time, you can enforce this behavior and save memory by using the oneof feature.

To define a oneof in your .proto you use the oneof keyword followed by your oneof name, in this case test_oneof:

message SampleMessage {

oneof test_oneof {

string name = 4;

SubMessage sub_message = 9;

}

}

You then add your oneof fields to the oneof definition. You can add fields of any type, except map fields and repeated fields.

In your generated code, oneof fields have the same getters and setters as regular fields. You also get a special method for checking which value (if any) in the oneof is set.

Maps

If you want to create an associative map as part of your data definition, protocol buffers provides a handy shortcut syntax:

map<key_type, value_type> map_field = N;

- The

key_typecan be any integral or string type (so, any scalar type except for floating point types and bytes). Note thatenumis not a validkey_type. - The

value_typecan be any type except anothermap.

So, for example, if you wanted to create a map of projects where each Project message is associated with a string key, you could define it like this:

map<string, Project> projects = 3;

- Map fields cannot be

repeated. - Wire format ordering and map iteration ordering of map values is undefined, so you cannot rely on your map items being in a particular order.

- When generating text format for a

.proto, maps are sorted by key. Numeric keys are sorted numerically. - When parsing from the wire or when merging, if there are duplicate map keys the last key seen is used. When parsing a map from text format, parsing may fail if there are duplicate keys.

- If you provide a key but no value for a map field, the behavior when the field is serialized is language-dependent. In C++, Java, and Python the default value for the type is serialized, while in other languages nothing is serialized.

Packages

You can add an optional package specifier to a .proto file to prevent name clashes between protocol message types.

package foo.bar;

message Open { ... }

You can then use the package specifier when defining fields of your message type:

message Foo {

...

foo.bar.Open open = 1;

...

}

The way a package specifier affects the generated code depends on your chosen language:

- In C++ the generated classes are wrapped inside a C++ namespace. For example,

Openwould be in the namespacefoo::bar. - In Java, the package is used as the Java package, unless you explicitly provide an option

java_packagein your.protofile. - In Go, the package is used as the Go package name, unless you explicitly provide an option

go_packagein your.protofile. - …

Defining Services

If you want to use your message types with an RPC (Remote Procedure Call) system, you can define an RPC service interface in a .proto file and the protocol buffer compiler will generate service interface code and stubs in your chosen language. So, for example, if you want to define an RPC service with a method that takes your SearchRequest and returns a SearchResponse, you can define it in your .proto file as follows:

service SearchService {

rpc Search(SearchRequest) returns (SearchResponse);

}

The most straightforward RPC system to use with protocol buffers is gRPC: a language- and platform-neutral open source RPC system developed at Google. gRPC works particularly well with protocol buffers and lets you generate the relevant RPC code directly from your .proto files using a special protocol buffer compiler plugin.

By default, the protocol compiler will then generate an abstract interface called SearchService and a corresponding “stub” implementation. The stub forwards all calls to an RpcChannel, which in turn is an abstract interface that you must define yourself in terms of your own RPC system. For example, you might implement an RpcChannel which serializes the message and sends it to a server via HTTP. In other words, the generated stub provides a type-safe interface for making protocol-buffer-based RPC calls, without locking you into any particular RPC implementation. So, in C++, you might end up with code like this:

using google::protobuf;

protobuf::RpcChannel* channel;

protobuf::RpcController* controller;

SearchService* service;

SearchRequest request;

SearchResponse response;

void DoSearch() {

// You provide classes MyRpcChannel and MyRpcController, which implement

// the abstract interfaces protobuf::RpcChannel and protobuf::RpcController.

channel = new MyRpcChannel("somehost.example.com:1234");

controller = new MyRpcController;

// The protocol compiler generates the SearchService class based on the

// definition given above.

service = new SearchService::Stub(channel);

// Set up the request.

request.set_query("protocol buffers");

// Execute the RPC.

service->Search(controller, request, response, protobuf::NewCallback(&Done));

}

void Done() {

delete service;

delete channel;

delete controller;

}

All service classes also implement the Service interface, which provides a way to call specific methods without knowing the method name or its input and output types at compile time. On the server side, this can be used to implement an RPC server with which you could register services.

using google::protobuf;

class ExampleSearchService : public SearchService {

public:

void Search(protobuf::RpcController* controller,

const SearchRequest* request,

SearchResponse* response,

protobuf::Closure* done) {

if (request->query() == "google") {

response->add_result()->set_url("http://www.google.com");

} else if (request->query() == "protocol buffers") {

response->add_result()->set_url("http://protobuf.googlecode.com");

}

done->Run();

}

};

int main() {

// You provide class MyRpcServer. It does not have to implement any

// particular interface; this is just an example.

MyRpcServer server;

protobuf::Service* service = new ExampleSearchService;

server.ExportOnPort(1234, service);

server.Run();

delete service;

return 0;

}

There are also a number of ongoing third-party projects to develop RPC implementations for Protocol Buffers. For a list of links to projects we know about, see the third-party add-ons wiki page.

JSON

Proto3 supports a canonical encoding in JSON, making it easier to share data between systems.

https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/proto3#json

Options

Individual declarations in a .proto file can be annotated with a number of options. Options do not change the overall meaning of a declaration, but may affect the way it is handled in a particular context. The complete list of available options is defined in google/protobuf/descriptor.proto.

Here are a few of the most commonly used options:

optimize_for(file option): Can be set toSPEED,CODE_SIZE, orLITE_RUNTIME. This affects the C++ and Java code generators (and possibly third-party generators) in the following ways:SPEED (default): The protocol buffer compiler will generate code for serializing, parsing, and performing other common operations on your message types. This code is highly optimized.CODE_SIZE: The protocol buffer compiler will generate minimal classes and will rely on shared, reflection-based code to implement serialialization, parsing, and various other operations. The generated code will thus be much smaller than withSPEED, but operations will be slower. Classes will still implement exactly the same public API as they do inSPEEDmode. This mode is most useful in apps that contain a very large number.protofiles and do not need all of them to be blindingly fast.LITE_RUNTIME: The protocol buffer compiler will generate classes that depend only on the “lite” runtime library (libprotobuf-liteinstead oflibprotobuf). The lite runtime is much smaller than the full library (around an order of magnitude smaller) but omits certain features like descriptors and reflection. This is particularly useful for apps running on constrained platforms like mobile phones. The compiler will still generate fast implementations of all methods as it does in SPEED mode. Generated classes will only implement theMessageLiteinterface in each language, which provides only a subset of the methods of the fullMessageinterface.

option optimize_for = CODE_SIZE;

https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/proto3#options

Generating Your Classes

To generate the Java, Python, C++, Go, Ruby, Objective-C, or C# code you need to work with the message types defined in a .proto file, you need to run the protocol buffer compiler protoc on the .proto.

The Protocol Compiler is invoked as follows:

protoc --proto_path=IMPORT_PATH --cpp_out=DST_DIR --java_out=DST_DIR --python_out=DST_DIR --go_out=DST_DIR --ruby_out=DST_DIR --objc_out=DST_DIR --csharp_out=DST_DIR path/to/file.proto

IMPORT_PATHspecifies a directory in which to look for.protofiles when resolving import directives. If omitted, the current directory is used. Multiple import directories can be specified by passing the--proto_pathoption multiple times; they will be searched in order.-I=_IMPORT_PATH_can be used as a short form of--proto_path.- You can provide one or more output directives:

--cpp_outgenerates C++ code inDST_DIR. See the C++ generated code reference for more.--java_outgenerates Java code inDST_DIR. See the Java generated code reference for more.--go_outgenerates Go code inDST_DIR. See the Go generated code reference for more.- …

- You must provide one or more

.protofiles as input. Multiple.protofiles can be specified at once. Although the files are named relative to the current directory, each file must reside in one of theIMPORT_PATHsso that the compiler can determine its canonical name.

Encoding

This document describes the protocol buffer wire format, which defines the details of how your message is sent on the wire and how much space it consumes on disk. You probably don’t need to understand this to use protocol buffers in your application, but it’s useful information for doing optimizations.

A Simple Message

Let’s say you have the following very simple message definition:

message Test1 {

optional int32 a = 1;

}

In an application, you create a Test1 message and set a to 150. You then serialize the message to an output stream. If you were able to examine the encoded message, you’d see three bytes:

08 96 01

So far, so small and numeric – but what does it mean? If you use the Protoscope tool to dump those bytes, you’d get something like 1: 150. How does it know this is the contents of the message?

Base 128 Varints

Variable-width integers, or varints, are at the core of the wire format. They allow encoding unsigned 64-bit integers using anywhere between one and ten bytes, with small values using fewer bytes.

Each byte in the varint has a continuation bit that indicates if the byte that follows it is part of the varint. This is the most significant bit (MSB) of the byte (sometimes also called the sign bit). The lower 7 bits are a payload; the resulting integer is built by appending together the 7-bit payloads of its constituent bytes.

So, for example, here is the number 1, encoded as 01 – it’s a single byte, so the MSB is not set:

0000 0001

^ msb

And here is 150, encoded as 9601 – this is a bit more complicated:

10010110 00000001

^ msb ^ msb

How do you figure out that this is 150? First you drop the MSB from each byte, as this is just there to tell us whether we’ve reached the end of the number (as you can see, it’s set in the first byte as there is more than one byte in the varint). Then we concatenate the 7-bit payloads, and interpret it as a little-endian, 64-bit unsigned integer:

10010110 00000001 // Original inputs.

0010110 0000001 // Drop continuation bits.

0000001 0010110 // Put into little-endian order.

10010110 // Concatenate.

128 + 16 + 4 + 2 = 150 // Interpret as integer.

Because varints are so crucial to protocol buffers, in protoscope syntax, we refer to them as plain integers. 150 is the same as 9601.

Message Structure

A protocol buffer message is a series of key-value pairs. The binary version of a message just uses the field’s number as the key – the name and declared type for each field can only be determined on the decoding end by referencing the message type’s definition(i.e. the .proto file). Protoscope does not have access to this information, so it can only provide the field numbers.

When a message is encoded, each key-value pair is turned into a record consisting of the field number, a wire type and a payload. The wire type tells the parser how big the payload after it is. This allows old parsers to skip over new fields they don’t understand. This type of scheme is sometimes called Tag-Length-Value, or TLV.

There are six wire types: VARINT, I64, LEN, SGROUP, EGROUP, and I32

| ID | Name | Used For |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | VARINT | int32, int64, uint32, uint64, sint32, sint64, bool, enum |

| 1 | I64 | fixed64, sfixed64, double |

| 2 | LEN | string, bytes, embedded messages, packed repeated fields |

| 3 | SGROUP | group start (deprecated) |

| 4 | EGROUP | group end (deprecated) |

| 5 | I32 | fixed32, sfixed32, float |

The “tag” of a record is encoded as a varint formed from the field number and the wire type via the formula (field_number << 3) | wire_type. In other words, after decoding the varint representing a field, the low 3 bits tell us the wire type, and the rest of the integer tells us the field number.

Now let’s look at our simple example again. You now know that the first number in the stream is always a varint key, and here it’s 08, or (dropping the MSB):

000 1000

You take the last three bits to get the wire type (0) and then right-shift by three to get the field number (1). Protoscope represents a tag as an integer followed by a colon and the wire type, so we can write the above bytes as 1:VARINT.

Because the wire type is 0, or VARINT, we know that we need to decode a varint to get the payload. As we saw above, the bytes 9601 varint-decode to 150, giving us our record. We can write it in Protoscope as 1:VARINT 150.

在线解码工具 (protobuf-decoder)

https://github.com/pawitp/protobuf-decoder

https://protobuf-decoder.netlify.app/

Protoscope

Protoscope is a simple, human-editable language for representing and emitting the Protobuf wire format. It is inspired by, and is significantly based on, DER ASCII, a similar tool for working with DER and BER, wire formats of ASN.1.

Unlike most Protobuf tools, it is normally ignorant of schemata specified in .proto files; it has just enough knowledge of the wire format to provide primitives for constructing messages (such as field tags, varints, and length prefixes). A disassembler is included that uses heuristics to try convert encoded Protobuf into Protoscope, although the heuristics are necessarily imperfect.

We provide the Go package github.com/protocolbuffers/protoscope, as well as the protoscope tool, which can be installed with the Go tool via

go install github.com/protocolbuffers/protoscope/cmd/protoscope...@latest

$which protoscope

~/go/bin/protoscope

$protoscope -h

Usage: protoscope [-s] [OPTION...] [INPUT]

Assemble a Protoscope file to binary, or inspect binary data as Protoscope text.

Run with -spec to learn more about the Protoscope language.

-all-fields-are-messages

try really hard to disassemble all fields as messages

-descriptor-set string

path to a file containing an encoded FileDescriptorSet, for aiding disassembly

-explicit-length-prefixes

emit literal length prefixes instead of braces

-explicit-wire-types

include an explicit wire type for every field

-message-type string

full name of a type in the FileDescriptorSet given by -descriptor-set;

the decoder will assume that the input file is an encoded binary proto

of this type for the purposes of providing better output

-no-groups

do not try to disassemble groups

-no-quoted-strings

assume no fields in the input proto are strings

-o string

output file to use (defaults to stdout)

-print-enum-names

prints out enum value names, if using -message-type

-print-field-names

prints out field names, if using -message-type

-s whether to treat the input as a Protoscope source file

-spec

opens the Protoscope spec in $PAGER

Exploring Binary Dumps

Sometimes, while working on a library that emits wire format, it may be necessary to debug the precise output of a test failure. If your test prints out a hex string, you can use the xxd command to turn it into raw binary data and pipe it into protoscope.

Consider the following example of a message with a google.protobuf.Any field:

$ cat hexdata.txt

0a400a26747970652e676f6f676c65617069732e636f6d2f70726f746f332e546573744d65737361676512161005420e65787065637465645f76616c756500000000

$ xxd -r -ps hexdata.txt | protoscope

1: {

1: {"type.googleapis.com/proto3.TestMessage"}

2: {`1005420e65787065637465645f76616c756500000000`}

}

$ xxd -r -ps <<< "1005420e65787065637465645f76616c756500000000" | protoscope

2: 5

8: {"expected_value"}

`00000000`

If your test failure output is made up of C-style escapes and text, the printf command can be used instead of xxd:

$ printf '\x10\x05B\x0eexpected_value\x00\x00\x00\x00' | protoscope

2: 5

8: {"expected_value"}

`00000000`

The protoscope command has many flags for refining the heuristic used to decode the binary.

If an encoded FileDescriptorSet proto is available that contains your message’s type, you can use it to get schema-aware decoding:

$ cat hexdata.txt

086510661867206828d20130d4013d6b000000416c000000000000004d6d000000516e000000000000005d0000de42610000000000005c40680172033131357a0331313683018801758401

$ xxd -r -ps hexdata.txt | protoscope \

-descriptor-set path/to/fds.pb -message-type unittest.TestAllTypes \

-print-field-names

1: 101 # optional_int32

2: 102 # optional_int64

3: 103 # optional_uint32

4: 104 # optional_uint64

5: 105z # optional_sint32

6: 106z # optional_sint64

7: 107i32 # optional_fixed32

8: 108i64 # optional_fixed64

9: 109i32 # optional_sfixed32

10: 110i64 # optional_sfixed64

11: 111.0i32 # optional_float, 0x42de0000i32

12: 112.0 # optional_double, 0x405c000000000000i64

13: true # optional_bool

14: {"115"} # optional_string

15: {"116"} # optional_bytes

16: !{ # optionalgroup

17: 117 # a

}

You can get an encoded FileDescriptorSet by invoking

protoc -Ipath/to/imported/protos -o my_fds.pb my_proto.proto

Modifying Existing Files

$ xxd foo.bin

00000000: 082a 1213 d202 106d 7920 6177 6573 6f6d .*.....my awesom

00000010: 6520 7072 6f74 6f e proto

$ protoscope foo.bin > foo.txt # Disassemble.

$ cat foo.txt

1: 42

2: {

42: {"my awesome proto"}

}

$ vim foo.txt # Make some edits.

$ cat foo.txt

1: 43

2: {

42: {"my even more awesome awesome proto"}

}

$ protoscope -s foo.txt > foo.bin # Reassemble.

$ xxd foo.bin

00000000: 082b 1225 d202 226d 7920 6576 656e 206d .+.%.."my even m

00000010: 6f72 6520 6177 6573 6f6d 6520 6177 6573 ore awesome awes

00000020: 6f6d 6520 7072 6f74 6f ome proto

Other

--proto_path

Protocol Buffer Basics: C++

Defining Your Protocol Format

// Copyright (C) 2021 $company Inc. All rights reserved.

//

// This is a sample protobuf source code.

// addressbook.proto

syntax = "proto3";

package demo;

message Person {

string name = 1;

int32 id = 2;

string email = 3;

enum PhoneType {

MOBILE = 0;

HOME = 1;

WORK = 2;

}

message PhoneNumber {

string number = 1;

PhoneType type = 2;

}

repeated PhoneNumber phones = 4;

}

message AddressBook {

repeated Person people = 1;

}

-

The

.protofile starts with apackagedeclaration, which helps to prevent naming conflicts between different projects. In C++, your generated classes will be placed in anamespacematching the package name. -

Next, you have your message definitions. A message is just an aggregate containing a set of typed fields. Many standard simple data types are available as field types, including

bool,int32,float,double, andstring. You can also add further structure to your messages by using other message types as field types – in the above example thePersonmessage containsPhoneNumbermessages, while theAddressBookmessage containsPersonmessages. You can even define message types nested inside other messages – as you can see, thePhoneNumbertype is defined insidePerson. You can also defineenumtypes if you want one of your fields to have one of a predefined list of values – here you want to specify that a phone number can be one ofMOBILE,HOME, orWORK. -

The “ = 1”, “ = 2” markers on each element identify the unique “tag” that field uses in the binary encoding. Tag numbers 1-15 require one less byte to encode than higher numbers, so as an optimization you can decide to use those tags for the commonly used or repeated elements, leaving tags 16 and higher for less-commonly used optional elements. Each element in a repeated field requires re-encoding the tag number, so repeated fields are particularly good candidates for this optimization.

-

Each field must be annotated with one of the following modifiers:

optional: the field may or may not be set. If an optional field value isn’t set, a default value is used. For simple types, you can specify your own default value, as we’ve done for the phone number type in the example. Otherwise, a system default is used:zerofor numeric types,the empty stringfor strings,falsefor bools. For embedded messages, the default value is always the “default instance” or “prototype” of the message, which has none of its fields set. Calling the accessor to get the value of an optional (or required) field which has not been explicitly set always returns that field’s default value.repeated: the field may be repeated any number of times (including zero). The order of the repeated values will be preserved in the protocol buffer. Think of repeated fields as dynamically sized arrays.required: a value for the field must be provided, otherwise the message will be considered “uninitialized”. Iflibprotobufis compiled indebugmode, serializing an uninitialized message will cause an assertion failure. In optimized builds, the check is skipped and the message will be written anyway. However, parsing an uninitialized message will always fail (by returning false from the parse method). Other than this, a required field behaves exactly like anoptionalfield.

Note: Required Is Forever You should be very careful about marking fields as required. If at some point you wish to stop writing or sending a

requiredfield, it will be problematic to change the field to an optional field – old readers will consider messages without this field to be incomplete and may reject or drop them unintentionally. You should consider writing application-specific custom validation routines for your buffers instead. Within Google, required fields are strongly disfavored; most messages defined in proto2 syntax useoptionalandrepeatedonly. (Proto3 does not support required fields at all.)

Compiling Your Protocol Buffers

-

Now that you have a

.proto, the next thing you need to do is generate the classes you’ll need to read and writeAddressBook(and hencePersonandPhoneNumber) messages. To do this, you need to run the protocol buffer compilerprotocon your.proto: -

If you haven’t installed the compiler, download the package and follow the instructions in the README.

$ protoc --version

libprotoc 3.15.8

- Now run the compiler, specifying the destination directory (where you want the generated code to go), and the path to your

.proto. This generates the following files in your specified destination directory:addressbook.pb.h, the header which declares your generated classes.addressbook.pb.cc, which contains the implementation of your classes.

#!/bin/bash

PROTOCOL_DIR=./

PROTOCOL_SRC_DIR=../src_protocol

PROTOCOL_FILES="addressbook.proto"

function Proc {

for file in $1

do

protoc --cpp_out=$PROTOCOL_SRC_DIR --proto_path=$PROTOCOL_DIR $file

if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

echo "protoc $file failed"

exit 1

fi

done

}

Proc "$PROTOCOL_FILES"

echo "ok"

The Protocol Buffer API

Let’s look at some of the generated code and see what classes and functions the compiler has created for you. If you look in addressbook.pb.h, you can see that you have a class for each message you specified in addressbook.proto. Looking closer at the Person class, you can see that the compiler has generated accessors for each field. For example, for the name, id, email, and phones fields, you have these methods:

// string name = 1;

void clear_name();

const std::string& name() const;

void set_name(const std::string& value);

void set_name(std::string&& value);

void set_name(const char* value);

void set_name(const char* value, size_t size);

std::string* mutable_name();

std::string* release_name();

void set_allocated_name(std::string* name);

private:

const std::string& _internal_name() const;

void _internal_set_name(const std::string& value);

std::string* _internal_mutable_name();

// int32 id = 2;

void clear_id();

::PROTOBUF_NAMESPACE_ID::int32 id() const;

void set_id(::PROTOBUF_NAMESPACE_ID::int32 value);

// repeated .demo.Person.PhoneNumber phones = 4;

inline int Person::_internal_phones_size() const {

return phones_.size();

}

inline int Person::phones_size() const {

return _internal_phones_size();

}

inline void Person::clear_phones() {

phones_.Clear();

}

inline ::demo::Person_PhoneNumber* Person::mutable_phones(int index) {

// @@protoc_insertion_point(field_mutable:demo.Person.phones)

return phones_.Mutable(index);

}

inline ::PROTOBUF_NAMESPACE_ID::RepeatedPtrField< ::demo::Person_PhoneNumber >*

Person::mutable_phones() {

// @@protoc_insertion_point(field_mutable_list:demo.Person.phones)

return &phones_;

}

inline const ::demo::Person_PhoneNumber& Person::_internal_phones(int index) const {

return phones_.Get(index);

}

inline const ::demo::Person_PhoneNumber& Person::phones(int index) const {

// @@protoc_insertion_point(field_get:demo.Person.phones)

return _internal_phones(index);

}

inline ::demo::Person_PhoneNumber* Person::_internal_add_phones() {

return phones_.Add();

}

inline ::demo::Person_PhoneNumber* Person::add_phones() {

// @@protoc_insertion_point(field_add:demo.Person.phones)

return _internal_add_phones();

}

inline const ::PROTOBUF_NAMESPACE_ID::RepeatedPtrField< ::demo::Person_PhoneNumber >&

Person::phones() const {

// @@protoc_insertion_point(field_list:demo.Person.phones)

return phones_;

}

// oneof para

enum : int {

kAFieldNumber = 1,

kBFieldNumber = 2,

};

// int32 a = 1;

bool has_a() const;

void clear_a();

::PROTOBUF_NAMESPACE_ID::int32 a() const;

void set_a(::PROTOBUF_NAMESPACE_ID::int32 value);

// string b = 2;

bool has_b() const;

void clear_b();

const std::string& b() const;

void set_b(const std::string& value);

void set_b(std::string&& value);

void set_b(const char* value);

void set_b(const char* value, size_t size);

std::string* mutable_b();

std::string* release_b();

void set_allocated_b(std::string* b);

// map<string, string> meta = 5;

inline int Person::meta_size() const {

return _internal_meta_size();

}

inline void Person::clear_meta() {

meta_.Clear();

}

inline const ::PROTOBUF_NAMESPACE_ID::Map< std::string, std::string >&

Person::meta() const {

// @@protoc_insertion_point(field_map:tutorial.Person.meta)

return _internal_meta();

}

inline ::PROTOBUF_NAMESPACE_ID::Map< std::string, std::string >*

Person::mutable_meta() {

// @@protoc_insertion_point(field_mutable_map:tutorial.Person.meta)

return _internal_mutable_meta();

}

- the

gettershave exactly the name as the field in lowercase - the

settermethods begin with set_ - There are also has_ methods for each singular (required or optional) field which return true if that field has been set

- Finally, each field has a clear_ method that un-sets the field back to its empty state.

- The

nameandemailfields have a couple of extra methods because they’re strings – a mutable_ getter that lets you get a direct pointer to the string, and an extra setter. - Repeated fields also have some special methods

- check the repeated field’s _size (in other words, how many phone numbers are associated with this Person).

- get a specified phone number using its index.

- update an existing phone number at the specified index.

- add another phone number to the message which you can then edit (repeated scalar types have an add_ that just lets you pass in the new value).

More: C++ Generated Code

Standard Message Methods

Each message class also contains a number of other methods that let you check or manipulate the entire message, including:

bool IsInitialized() const;: checks if all the required fields have been set.string DebugString() const;: returns a human-readable representation of the message, particularly useful for debugging.void CopyFrom(const Person& from);: overwrites the message with the given message’s values.void Clear();: clears all the elements back to the empty state.

These and the I/O methods described in the following section implement the Message interface shared by all C++ protocol buffer classes. For more info, see the complete API documentation for Message.

Parsing and Serialization

Finally, each protocol buffer class has methods for writing and reading messages of your chosen type using the protocol buffer binary format. These include:

bool SerializeToString(string* output) const;: serializes the message and stores the bytes in the given string. Note that the bytes are binary, not text; we only use the string class as a convenient container.bool ParseFromString(const string& data);: parses a message from the given string.bool SerializeToOstream(ostream* output) const;: writes the message to the given C++ ostream.bool ParseFromIstream(istream* input);: parses a message from the given C++ istream.

These are just a couple of the options provided for parsing and serialization. Again, see the Message API reference for a complete list.

Note: Protocol Buffers and Object Oriented Design Protocol buffer classes are basically dumb data holders (like structs in C); they don’t make good first class citizens in an object model. If you want to add richer behavior to a generated class, the best way to do this is to wrap the generated protocol buffer class in an application-specific class. Wrapping protocol buffers is also a good idea if you don’t have control over the design of the .proto file (if, say, you’re reusing one from another project). In that case, you can use the wrapper class to craft an interface better suited to the unique environment of your application: hiding some data and methods, exposing convenience functions, etc. You should never add behaviour to the generated classes by inheriting from them. This will break internal mechanisms and is not good object-oriented practice anyway.

Writing A Message

Now let’s try using your protocol buffer classes. The first thing you want your address book application to be able to do is write personal details to your address book file. To do this, you need to create and populate instances of your protocol buffer classes and then write them to an output stream.

Here is a program which reads an AddressBook from a file, adds one new Person to it based on user input, and writes the new AddressBook back out to the file again. The parts which directly call or reference code generated by the protocol compiler are highlighted.

- Notice the

GOOGLE_PROTOBUF_VERIFY_VERSIONmacro. It is good practice – though not strictly necessary – to execute this macro before using the C++ Protocol Buffer library. It verifies that you have not accidentally linked against a version of the library which is incompatible with the version of the headers you compiled with. If a version mismatch is detected, the program will abort. Note that every.pb.ccfile automatically invokes this macro on startup. - Also notice the call to

ShutdownProtobufLibrary()at the end of the program. All this does is delete any global objects that were allocated by the Protocol Buffer library. This is unnecessary for most programs, since the process is just going to exit anyway and the OS will take care of reclaiming all of its memory. However, if you use a memory leak checker that requires that every last object be freed, or if you are writing a library which may be loaded and unloaded multiple times by a single process, then you may want to force Protocol Buffers to clean up everything.

// ...

Reading A Message

Of course, an address book wouldn’t be much use if you couldn’t get any information out of it! This example reads the file created by the above example and prints all the information in it.

// ...

Extending a Protocol Buffer

https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/cpptutorial#extending-a-protocol-buffer

Optimization Tips

The C++ Protocol Buffers library is extremely heavily optimized. However, proper usage can improve performance even more. Here are some tips for squeezing every last drop of speed out of the library:

-

Reuse message objects when possible. Messages try to keep around any memory they allocate for reuse, even when they are cleared. Thus, if you are handling many messages with the same type and similar structure in succession, it is a good idea to reuse the same message object each time to take load off the memory allocator. However, objects can become bloated over time, especially if your messages vary in “shape” or if you occasionally construct a message that is much larger than usual. You should monitor the sizes of your message objects by calling the SpaceUsed method and delete them once they get too big.

-

Your system’s memory allocator may not be well-optimized for allocating lots of small objects from multiple threads. Try using Google’s tcmalloc instead.

Advanced Usage

Protocol buffers have uses that go beyond simple accessors and serialization. Be sure to explore the C++ API reference to see what else you can do with them.

One key feature provided by protocol message classes is reflection. You can iterate over the fields of a message and manipulate their values without writing your code against any specific message type. One very useful way to use reflection is for converting protocol messages to and from other encodings, such as XML or JSON. A more advanced use of reflection might be to find differences between two messages of the same type, or to develop a sort of “regular expressions for protocol messages” in which you can write expressions that match certain message contents. If you use your imagination, it’s possible to apply Protocol Buffers to a much wider range of problems than you might initially expect!

Reflection is provided by the Message::Reflection interface.

C++ API

https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/reference/cpp

关键结构

RepeatedField / RepeatedPtrField

https://developers.google.com/protocol-buffers/docs/reference/cpp/google.protobuf.repeated_field

RRepeatedField is used to represent repeated fields of a primitive type (in other words, everything except strings and nested Messages). RepeatedPtrField is like RepeatedField, but used for repeated strings or Messages.

RepeatedField和RepeatedPtrField是用来操作管理repeated类型字段的class。它们的功能和STL vector非常相似,不同的是针对Protocol Buffers做了很多相关的优化。RepeatedPtrField与STL vector特别不一样的地方在于,它对指针所有权的管理。- 通常来说,客户端不应该直接操作

RepeatedField对象,而是应该通过protoc生成的accessor functions来操作。

#include <google/protobuf/repeated_field.h>

namespace google::protobuf

template <typename Element>

class RepeatedField

RepeatedField()

explicit RepeatedField(Arena * arena)

RepeatedField(const RepeatedField & other)

template RepeatedField(Iter begin, const Iter & end)

typedef Element * iterator // STL-like iterator support.

typedef Element value_type

typedef value_type & reference

typedef value_type * pointer

typedef int size_type

typedef ptrdiff_t difference_type

const typedef Element * const_iterator

const typedef value_type & const_reference

const typedef value_type * const_pointer

typedef std::reverse_iterator< const_iterator > // Reverse iterator support.

typedef std::reverse_iterator< iterator > reverse_iterator

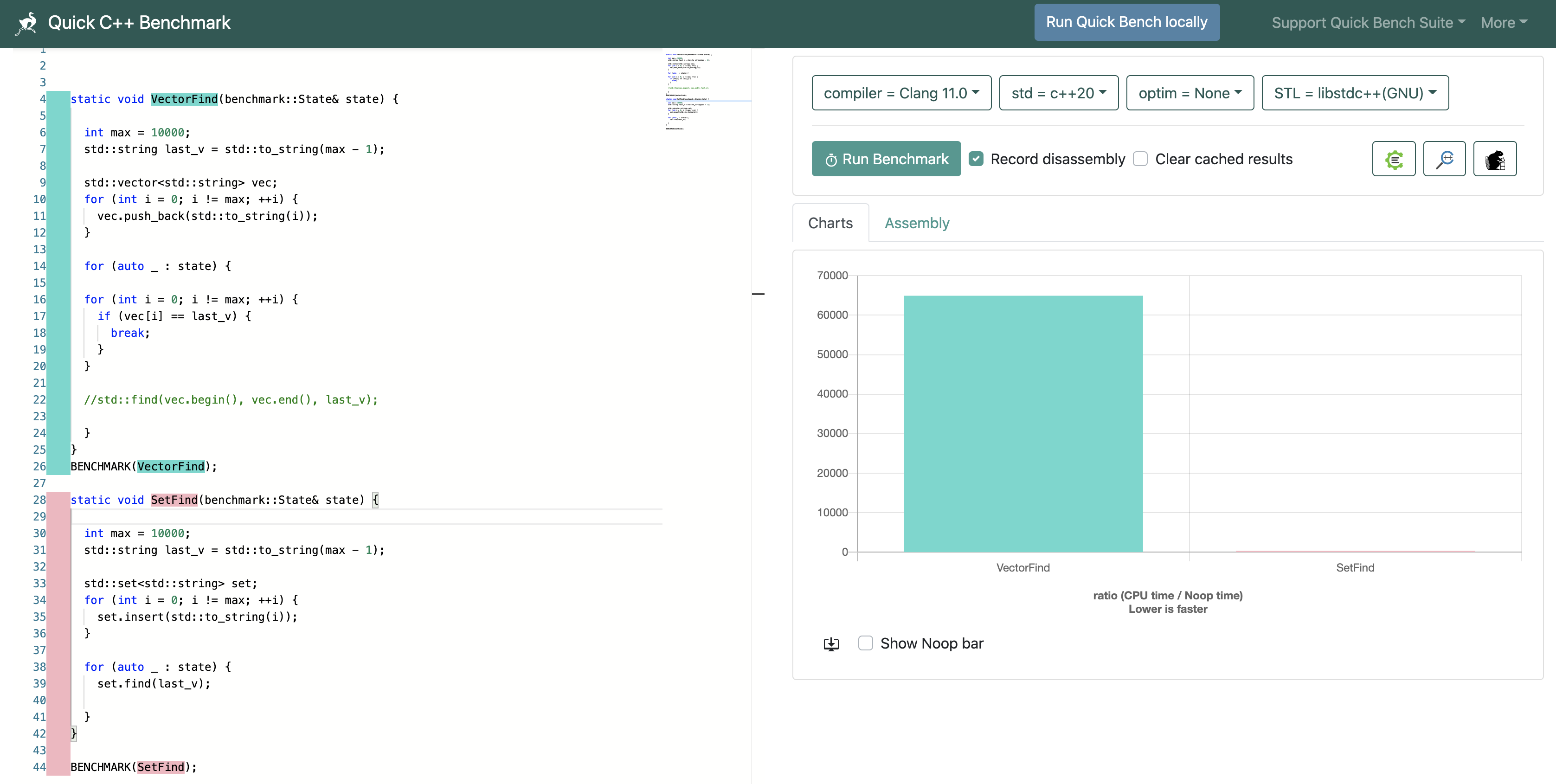

性能测试

在线工具 Quick C++ Benchmark

static void VectorFind(benchmark::State& state) {

int max = 10000;

std::string last_v = std::to_string(max - 1);

std::vector<std::string> vec;

for (int i = 0; i != max; ++i) {

vec.push_back(std::to_string(i));

}

for (auto _ : state) {

for (int i = 0; i != max; ++i) {

if (vec[i] == last_v) {

break;

}

}

//std::find(vec.begin(), vec.end(), last_v);

}

}

BENCHMARK(VectorFind);

static void SetFind(benchmark::State& state) {

int max = 10000;

std::string last_v = std::to_string(max - 1);

std::set<std::string> set;

for (int i = 0; i != max; ++i) {

set.insert(std::to_string(i));

}

for (auto _ : state) {

set.find(last_v);

}

}

BENCHMARK(SetFind);

Celero

- 测试代码:

$ ./celero_benchmark

Celero

Timer resolution: 0.001000 us

| Group | Experiment | Prob. Space | Samples | Iterations | Baseline | us/Iteration | Iterations/sec | RAM (bytes) |

|:--------------:|:---------------:|:---------------:|:---------------:|:---------------:|:---------------:|:---------------:|:---------------:|:---------------:|

|find | vector | Null | 1 | 1 | 1.00000 | 172.00000 | 5813.95 | 51277824 |

|find | pb_repeated | Null | 1 | 1 | 73.59302 | 12658.00000 | 79.00 | 51777536 |

|find | set | Null | 10 | 20 | 0.00058 | 0.10000 | 10000000.00 | 51777536 |

|find | unordered_set | Null | 10 | 20 | 0.00029 | 0.05000 | 20000000.00 | 51777536 |

|find | flat_set | Null | 10 | 20 | 0.00058 | 0.10000 | 10000000.00 | 51777536 |

Completed in 00:00:00.028138

vector/map/unordered_map/pb repeated

- 测试代码:

$ perf stat -B ./press

pid(2008)

pb repeated

find it(999999) cnt(999999)

elapse(0.280948s)

Performance counter stats for './press':

606.010051 task-clock (msec) # 0.858 CPUs utilized

730 context-switches # 0.001 M/sec

0 cpu-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

123,296 page-faults # 0.203 M/sec

<not supported> cycles

<not supported> instructions

<not supported> branches

<not supported> branch-misses

0.706142993 seconds time elapsed

$ perf stat -B ./press

pid(2277)

map

find it(999999) cnt(999999)

elapse(0.0260171s)

Performance counter stats for './press':

457.361877 task-clock (msec) # 0.914 CPUs utilized

572 context-switches # 0.001 M/sec

0 cpu-migrations # 0.000 K/sec

19,711 page-faults # 0.043 M/sec

<not supported> cycles

<not supported> instructions

<not supported> branches

<not supported> branch-misses

0.500588136 seconds time elapsed

对比 FlatBuffers

国内有什么大公司使用flatbuffers吗?它和protobuffer之间如何取舍?

优势:fb 是一种无需解码的二进制格式,解码性能很高,适合使用在频繁解码的场景。 不足:fb 的接口易用性较差,编码性能比 pb 低很多,编码后的数据长度也比 pb 长。

- https://github.com/google/flatbuffers

Arena Allocation

引入 Arena 支持,减少大对象释放开销,可参考:C++ Arena Allocation Guide

Arena 就是由 protbuf 库去接管 pb 对象的内存管理。它的原理很简单,是预先分配一个内存块;解析消息和构建消息等触发对象创建时是在已分配好的内存块上 placement new 出来;arena 对象析构时会释放所有内存,理想情况下不需要运行任何被包含对象的析构函数。

适用场景:

pb 结构比较复杂,repeated 类型字段包含的数据个数比较多。(注意:并非所有场景都是正收益)

好处:

- 减少复杂 pb 对象中多次 malloc/free 和析构带来的系统开销

- 减少内存碎片

- pb 对象的内存连续,cache line友好,读取性能高

proto 文件声明

cc_enable_arenas (file option): Enables arena allocation for C++ generated code. Refer proto3

option cc_enable_arenas = true;

线程安全

This is a thread-safe implementation: multiple threads may allocate from the arena concurrently. Destruction is not thread-safe and the destructing thread must synchronize with users of the arena first.

arena 头文件部分注释

Arena message allocation protocol

// Arena allocator. Arena allocation replaces ordinary (heap-based) allocation

// with new/delete, and improves performance by aggregating allocations into

// larger blocks and freeing allocations all at once. Protocol messages are

// allocated on an arena by using Arena::CreateMessage<T>(Arena*), below, and

// are automatically freed when the arena is destroyed.

//

// This is a thread-safe implementation: multiple threads may allocate from the

// arena concurrently. Destruction is not thread-safe and the destructing

// thread must synchronize with users of the arena first.

//

// An arena provides two allocation interfaces: CreateMessage<T>, which works

// for arena-enabled proto2 message types as well as other types that satisfy

// the appropriate protocol (described below), and Create<T>, which works for

// any arbitrary type T. CreateMessage<T> is better when the type T supports it,

// because this interface (i) passes the arena pointer to the created object so

// that its sub-objects and internal allocations can use the arena too, and (ii)

// elides the object's destructor call when possible. Create<T> does not place

// any special requirements on the type T, and will invoke the object's

// destructor when the arena is destroyed.

//

// The arena message allocation protocol, required by CreateMessage<T>, is as

// follows:

//

// - The type T must have (at least) two constructors: a constructor with no

// arguments, called when a T is allocated on the heap; and a constructor with

// a Arena* argument, called when a T is allocated on an arena. If the

// second constructor is called with a NULL arena pointer, it must be

// equivalent to invoking the first (no-argument) constructor.

//

// - The type T must have a particular type trait: a nested type

// |InternalArenaConstructable_|. This is usually a typedef to |void|. If no

// such type trait exists, then the instantiation CreateMessage<T> will fail

// to compile.

//

// - The type T *may* have the type trait |DestructorSkippable_|. If this type

// trait is present in the type, then its destructor will not be called if and

// only if it was passed a non-NULL arena pointer. If this type trait is not

// present on the type, then its destructor is always called when the

// containing arena is destroyed.

//

// - One- and two-user-argument forms of CreateMessage<T>() also exist that

// forward these constructor arguments to T's constructor: for example,

// CreateMessage<T>(Arena*, arg1, arg2) forwards to a constructor T(Arena*,

// arg1, arg2).

//

// This protocol is implemented by all arena-enabled proto2 message classes as

// well as protobuf container types like RepeatedPtrField and Map. The protocol

// is internal to protobuf and is not guaranteed to be stable. Non-proto types

// should not rely on this protocol.

//

// Do NOT subclass Arena. This class will be marked as final when C++11 is

// enabled.

class PROTOBUF_EXPORT Arena {

// ...

};

CreateMessage

// protobuf/arena.h

// API to create proto2 message objects on the arena. If the arena passed in

// is NULL, then a heap allocated object is returned. Type T must be a message

// defined in a .proto file with cc_enable_arenas set to true, otherwise a

// compilation error will occur.

//

// RepeatedField and RepeatedPtrField may also be instantiated directly on an

// arena with this method.

//

// This function also accepts any type T that satisfies the arena message

// allocation protocol, documented above.

template <typename T, typename... Args>

PROTOBUF_ALWAYS_INLINE static T* CreateMessage(Arena* arena, Args&&... args) {

static_assert(

InternalHelper<T>::is_arena_constructable::value,

"CreateMessage can only construct types that are ArenaConstructable");

// We must delegate to CreateMaybeMessage() and NOT CreateMessageInternal()

// because protobuf generated classes specialize CreateMaybeMessage() and we

// need to use that specialization for code size reasons.

return Arena::CreateMaybeMessage<T>(arena, std::forward<Args>(args)...);

}

// Allocate and also optionally call on_arena_allocation callback with the

// allocated type info when the hooks are in place in ArenaOptions and

// the cookie is not null.

template <typename T>

PROTOBUF_ALWAYS_INLINE void* AllocateInternal(bool skip_explicit_ownership) {

const size_t n = internal::AlignUpTo8(sizeof(T));

AllocHook(RTTI_TYPE_ID(T), n);

// Monitor allocation if needed.

if (skip_explicit_ownership) {

return impl_.AllocateAligned(n);

} else {

return impl_.AllocateAlignedAndAddCleanup(

n, &internal::arena_destruct_object<T>);

}

}

template <typename T, typename... Args>

PROTOBUF_ALWAYS_INLINE T* DoCreateMessage(Args&&... args) {

return InternalHelper<T>::Construct(

AllocateInternal<T>(InternalHelper<T>::is_destructor_skippable::value),

this, std::forward<Args>(args)...);

}

template <typename T, typename... Args>

PROTOBUF_ALWAYS_INLINE static T* CreateMessageInternal(Arena* arena,

Args&&... args) {

static_assert(

InternalHelper<T>::is_arena_constructable::value,

"CreateMessage can only construct types that are ArenaConstructable");

if (arena == NULL) {

return new T(nullptr, std::forward<Args>(args)...);

} else {

return arena->DoCreateMessage<T>(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

}

}

// This specialization for no arguments is necessary, because its behavior is

// slightly different. When the arena pointer is nullptr, it calls T()

// instead of T(nullptr).

template <typename T>

PROTOBUF_ALWAYS_INLINE static T* CreateMessageInternal(Arena* arena) {

static_assert(

InternalHelper<T>::is_arena_constructable::value,

"CreateMessage can only construct types that are ArenaConstructable");

if (arena == NULL) {

return new T();

} else {

return arena->DoCreateMessage<T>();

}

}

// CreateMessage<T> requires that T supports arenas, but this private method

// works whether or not T supports arenas. These are not exposed to user code

// as it can cause confusing API usages, and end up having double free in

// user code. These are used only internally from LazyField and Repeated

// fields, since they are designed to work in all mode combinations.

template <typename Msg, typename... Args>

PROTOBUF_ALWAYS_INLINE static Msg* DoCreateMaybeMessage(Arena* arena,

std::true_type,

Args&&... args) {

return CreateMessageInternal<Msg>(arena, std::forward<Args>(args)...);

}

template <typename T, typename... Args>

PROTOBUF_ALWAYS_INLINE static T* DoCreateMaybeMessage(Arena* arena,

std::false_type,

Args&&... args) {

return CreateInternal<T>(arena, std::forward<Args>(args)...);

}

template <typename T, typename... Args>

PROTOBUF_ALWAYS_INLINE static T* CreateMaybeMessage(Arena* arena,

Args&&... args) {

return DoCreateMaybeMessage<T>(arena, is_arena_constructable<T>(),

std::forward<Args>(args)...);

}

ArenaOptions

// protobuf/arena.h

// ArenaOptions provides optional additional parameters to arena construction

// that control its block-allocation behavior.

struct ArenaOptions {

// This defines the size of the first block requested from the system malloc.

// Subsequent block sizes will increase in a geometric series up to a maximum.

size_t start_block_size;

// This defines the maximum block size requested from system malloc (unless an

// individual arena allocation request occurs with a size larger than this

// maximum). Requested block sizes increase up to this value, then remain

// here.

size_t max_block_size;

// An initial block of memory for the arena to use, or NULL for none. If

// provided, the block must live at least as long as the arena itself. The

// creator of the Arena retains ownership of the block after the Arena is

// destroyed.

char* initial_block;

// The size of the initial block, if provided.

size_t initial_block_size;

// A function pointer to an alloc method that returns memory blocks of size

// requested. By default, it contains a ptr to the malloc function.

//

// NOTE: block_alloc and dealloc functions are expected to behave like

// malloc and free, including Asan poisoning.

void* (*block_alloc)(size_t);

// A function pointer to a dealloc method that takes ownership of the blocks

// from the arena. By default, it contains a ptr to a wrapper function that

// calls free.

void (*block_dealloc)(void*, size_t);

ArenaOptions()

: start_block_size(kDefaultStartBlockSize),

max_block_size(kDefaultMaxBlockSize),

initial_block(NULL),

initial_block_size(0),

block_alloc(&::operator new),

block_dealloc(&internal::arena_free),

on_arena_init(NULL),

on_arena_reset(NULL),

on_arena_destruction(NULL),

on_arena_allocation(NULL) {}

private:

// Hooks for adding external functionality such as user-specific metrics

// collection, specific debugging abilities, etc.

// Init hook may return a pointer to a cookie to be stored in the arena.

// reset and destruction hooks will then be called with the same cookie

// pointer. This allows us to save an external object per arena instance and

// use it on the other hooks (Note: It is just as legal for init to return

// NULL and not use the cookie feature).

// on_arena_reset and on_arena_destruction also receive the space used in

// the arena just before the reset.

void* (*on_arena_init)(Arena* arena);

void (*on_arena_reset)(Arena* arena, void* cookie, uint64 space_used);

void (*on_arena_destruction)(Arena* arena, void* cookie, uint64 space_used);

// type_info is promised to be static - its lifetime extends to

// match program's lifetime (It is given by typeid operator).

// Note: typeid(void) will be passed as allocated_type every time we

// intentionally want to avoid monitoring an allocation. (i.e. internal

// allocations for managing the arena)

void (*on_arena_allocation)(const std::type_info* allocated_type,

uint64 alloc_size, void* cookie);

// Constants define default starting block size and max block size for

// arena allocator behavior -- see descriptions above.

static const size_t kDefaultStartBlockSize = 256;

static const size_t kDefaultMaxBlockSize = 8192;

friend void arena_metrics::EnableArenaMetrics(ArenaOptions*);

friend class Arena;

friend class ArenaOptionsTestFriend;

};

Why use arena allocation?

Memory allocation and deallocation constitutes a significant fraction of CPU time spent in protocol buffers code. By default, protocol buffers performs heap allocations for each message object, each of its subobjects, and several field types, such as strings. These allocations occur in bulk when parsing a message and when building new messages in memory, and associated deallocations happen when messages and their subobject trees are freed.

Arena-based allocation has been designed to reduce this performance cost. With arena allocation, new objects are allocated out of a large piece of preallocated memory called the arena. Objects can all be freed at once by discarding the entire arena, ideally without running destructors of any contained object (though an arena can still maintain a “destructor list” when required). This makes object allocation faster by reducing it to a simple pointer increment, and makes deallocation almost free. Arena allocation also provides greater cache efficiency: when messages are parsed, they are more likely to be allocated in continuous memory, which makes traversing messages more likely to hit hot cache lines.

To get these benefits you’ll need to be aware of object lifetimes and find a suitable granularity at which to use arenas (for servers, this is often per-request). You can find out more about how to get the most from arena allocation in Usage patterns and best practices.

Getting started

The protocol buffer compiler generates code for arena allocation for the messages in your file, as used in the following example.

#include <google/protobuf/arena.h>

{

google::protobuf::Arena arena;

MyMessage* message = google::protobuf::Arena::CreateMessage<MyMessage>(&arena);

// ...

}

The message object created by CreateMessage() exists for as long as arena exists, and you should not delete the returned message pointer. All of the message object’s internal storage (with a few exceptions) and submessages (for example, submessages in a repeated field within MyMessage) are allocated on the arena as well.

Currently, string fields store their data on the heap even when the containing message is on the arena. Unknown fields are also heap-allocated

For the most part, the rest of your code will be the same as if you weren’t using arena allocation.

Arena class API

You create message objects on the arena using the google::protobuf::Arena class. This class implements the following public methods.

Constructors

Arena(): Creates a new arena with default parameters, tuned for average use cases.Arena(const ArenaOptions& options): Creates a new arena that uses the specified allocation options. The options available inArenaOptionsinclude the ability to use an initial block of user-provided memory for allocations before resorting to the system allocator, control over the initial and maximum request sizes for blocks of memory, and allowing you to pass in custom block allocation and deallocation function pointers to build freelists and others on top of the blocks.

Allocation methods

template<typename T> static T* CreateMessage(Arena* arena): Creates a new protocol buffer object of message typeTon thearena.

If arena is not NULL, the returned message object is allocated on the arena, its internal storage and submessages (if any) will be allocated on the same arena, and its lifetime is the same as that of the arena. The object must not be deleted/freed manually: the arena owns the message object for lifetime purposes.

template<typename T> static T* Create(Arena* arena, args...): Similar toCreateMessage()but lets you create an object of any class on thearena, not just protocol buffer message types. For example, let’s say you have this C++ class:

class MyCustomClass {

MyCustomClass(int arg1, int arg2);

// ...

};

you can create an instance of it on the arena like this:

void func() {

// ...

google::protobuf::Arena arena;

MyCustomClass* c = google::protobuf::Arena::Create<MyCustomClass>(&arena, constructor_arg1, constructor_arg2);

// ...

}

template<typename T> static T* CreateArray(Arena* arena, size_t n): Ifarenais not NULL, this method allocates raw storage for n elements of type T and returns it. Thearenaowns the returned memory and will free it on its own destruction. Ifarenais NULL, this method allocates storage on the heap and the caller receives ownership.

T must have a trivial constructor: constructors are not called when the array is created on the arena.

“Owned list” methods

The following methods let you specify that particular objects or destructors are “owned” by the arena, ensuring that they are deleted or called when the arena itself is deleted。

template<typename T> void Own(T* object)template<typename T> void OwnDestructor(T* object)

Other methods

uint64 SpaceUsed() constuint64 Reset()template<typename T> Arena* GetArena()

Thread safety

google::protobuf::Arena’s allocation methods are thread-safe, and the underlying implementation goes to some length to make multithreaded allocation fast. The Reset() method is not thread-safe: the thread performing the arena reset must synchronize with all threads performing allocations or using objects allocated from that arena first.

Generated message class

The following message class members are changed or added when you enable arena allocation.

Message class methods

Message(Message&& other): If the source message is not onarena, the move constructor efficiently moves all fields from one message to another without making copies or heap allocations (the time complexity of this operation isO(number-of-declared-fields)). However, if the source message is onarena, it performs a deep copy of the underlying data. In both cases the source message is left in a valid but unspecified state.

移动构造函数 非 arena:移动语义,零拷贝 arena:深拷贝